What did Canal Mothers and Daughters Think about Voting?

We Don’t Know—they were too busy working

The eighteen hours a day, six days a week schedule on Pennsylvania’s anthracite canals didn’t leave much time for writing letters, keeping diaries, or generally putting their thoughts down on paper. So we don’t know what the girls and women who worked on the canals thought about the struggle for women to get the right to vote. There seems to be little doubt though, that they showed through their work that they considered themselves equal to men and every bit as capable of doing their jobs.

Canal folks in the 19th and early 20th centuries had a unique way of life. Whether they ran the mule-drawn canal boats or tended the locks, the men, women, and children on the canals worked and lived differently than nearly all the rest of Americans at that time.

One striking aspect of life on the canals was that women were as likely as men to do many of the jobs. Whether this was a corporate policy or just practicality, the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company (LCN), owner of the Lehigh and Delaware Canals, most of the boats and all of the locktender’s houses, seems to have worked with—and paid—women the same as they did men.

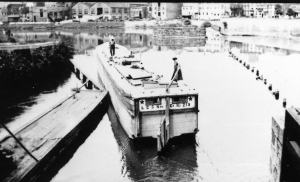

Martha “Hautie” Best steering their boat from the Delaware Canal into the Lehigh Navigation at Easton

Taking over at the tiller was common. Though steering a canal boat—either loaded or empty—required both skill and strength, many canal boat wives and daughters often did it. Walnutport’s Martha “Hautie” Best was not only adept at handling the somewhat tricky transition from the Delaware Canal into the Lehigh Navigation at Easton, she knew how to handle the harassment from swimmers and others on the canals who tried to hitch rides on her rudder.

“The worst I did was in Allentown,” she told C.P. Yoder, author of Delaware Canal Journal. “These two in a canoe grabbed my rudder. I said ‘please get off, it’s hard for me to steer.’ Well, they acted real smart, so I said if you don’t get off you’ll be real sorry…. So I went down and got the chamber potty and threw the whole darned thing on them.”

Her daughter Martha told the D&L’s Dennis Scholl, author of Tales of the Towpath, that she worked on her parents’ boat, driving the mules, steering, cooking, and helping to keep the records of what they delivered, from the age of eight until she was 21. In an interview in 2008, when she was 96, the retired teacher said that her father set aside the money he would have paid for a mule driver so that she could attend what was then Kutztown State Teachers College. But unlike canal boat children in the 19th century, who only went to school for a few months when the canal closed in winter, Martha Best lived with relatives in Walnutport during the school year while her parents boated.

In families that owned their boats, rather than leasing them from LCN, a woman whose husband died or became disabled could take over the running of the boat and continue the family business, thanks to an early 18th century Pennsylvania law about common property in a marriage. There are very few records of female captains, however.

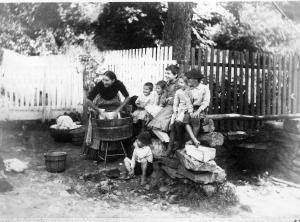

Female locktenders were far more common, particularly in the 20th century. In reality, the wives of the “official” male locktenders were frequently the ones actually running the locks for the entire time the canals were open. Locktenders got to live in the houses free of charge, but the monthly salary was small—seven dollars a month was usual in the 19th century, and finally reached $30 per month near the end of the canals’ run. This low pay often drove the fathers of locktender families to find work nearby that paid better, which left their wives and older children to operate the lock for eighteen hours a day. (The rack-and-pinion gears in the “doghouse” made it possible for them to move the lock gates that each weighed several tons.) In addition, locktender wives sold baked goods and fresh produce from their gardens to canal boaters, and often took in laundry, which was nearly impossible to do in the close confines of a wooden canal boat.

There are several documented instances of a widow or a daughter officially taking over a lock after the death of a husband or father. Eliza Jane Walck’s husband, the locktender at Lock 5 in Packerton, drowned in the lock in 1916. She moved her family to Lock 34 in Northampton for a year, and then took over Guard Lock 6 in North Catasauqua. Though her common law husband Harry Allen was the official locktender, he was also a full-time boat captain, so Eliza was in charge of the lock with a part-time helper. When the Navigation closed, she purchased the locktender’s house, which remained in her family until recently. Jennie Hontz took over Guard Lock 4 at Three Mile Dam after her husband died in the late 1920s. Her son later told canal researcher Wouter de Nie that she was also responsible for adjusting the feeder gates there to keep water flowing to the flour mill in Treichlers. Lewis Lentz took over Lock 36 in Catasauqua in 1926, but his daughter Annie did the actual tending until the lock was destroyed in the floods of 1942.

On the Delaware Canal, Flora Henry came to the double lock 15-16 at Smithtown, the second deepest on the canal, at the age of five. Her father became the locktender there in 1915, and she told C.P. Yoder that she began operating the canal gates at 14. When her father died in 1931, 21-year-old Flora became the locktender and locked through the last boats that navigated the Delaware Canal.

While the names and stories of most female “canallers” are lost to history, the hardworking women mentioned above give us a glimpse into what their lives were like. These women may not have thought of themselves as pioneers of equality, but they certainly helped the cause in their own way.

Join the Conversation!