The Women of the Silk Mills

By NCM Historian Martha Capwell Fox

In celebration of Women’s History Month, our history blogs for the next weeks will look at the roles women played in the development of industries in the D&L Corridor. We are excited to announce that this will also be the focus of the 2022 exhibit in the National Canal Museum. To begin with, here is the story of the hundred years of women’s work in the first major manufacturing industry to employ them—silk.

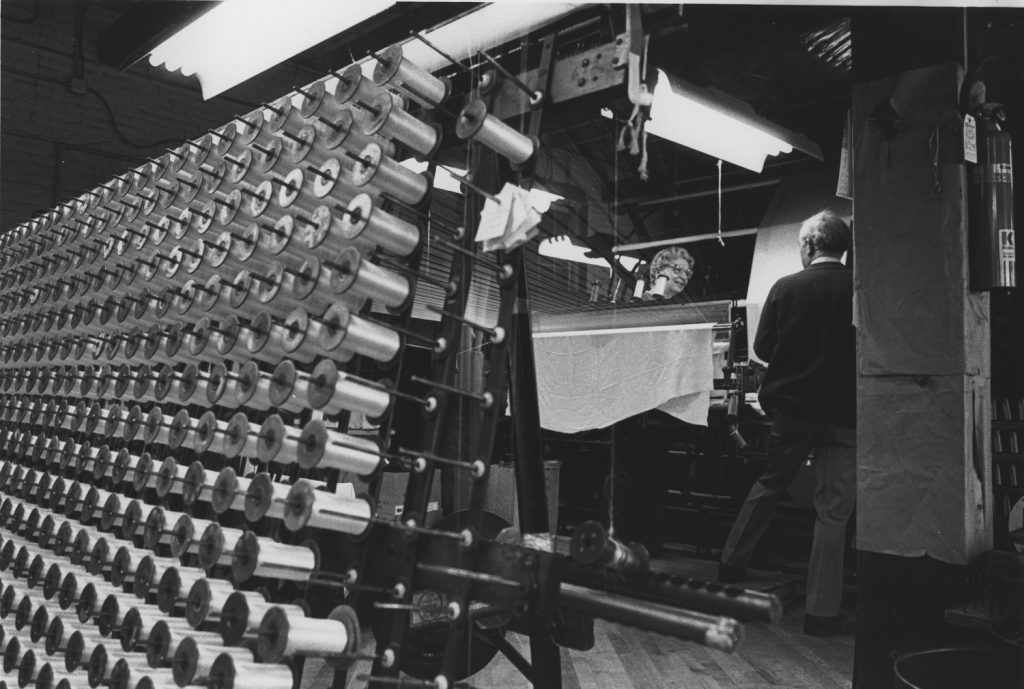

Irene Clauser, at work in the Catoir silk mill in Allentown in 1981. Ken Bloom, NCM Collection

This is Irene Clauser, at work in the Catoir silk mill in Allentown in 1981. At the time, she was in her late 70s, and spent her workdays carrying bobbins from the doubler machine on the left, up a flight of wooden stairs to the quilling machine on the second floor. This was her last job in a silk mill. Her first was in the 1920s, when she learned to be a warper in the former Dery silk mill in Northampton. Her working life in the silk industry spanned the decades from the time that eastern Pennsylvania led the world in producing silk goods, to a few years before Catoir, the last silk mill in the Lehigh Valley, closed in 1989.

Irene was sharp, lively, and loved a good joke. She was still working because she liked it, she said. (Full disclosure here: my father owned Catoir, Inc, and I worked in the mill in 1979-80.) It got her out of the house, in contact with other women her age, or near it, who also had the same work and life stories, and gave her something to do. She scoffed at the idea of retiring and moving into a senior living residence (”monkey houses”, she called them, “everybody knows everybody else’s business.”), and counted herself and her husband lucky that they still lived in the house where he grew up.

Irene’s husband Gordon had also worked as a weaver in the Northampton mill. She was proud of the fact that when she stopped working temporarily when their son was born in 1931, she was earning more ($.0.25 an hour), than he was. Over the years Irene ran a variety of mill machinery, and so found work whenever she wanted it, even as the number of silk mills dwindled by the 1970s. “What else would I do?” she said. “the mills are part of my life.”

Catherine McQuillan and Louis Capwell at the warper. Ken Bloom, NCM Collection

This is Catherine McQuillan, the warper at Catoir. One of thirteen children in the Gemmel family, she grew up across the street from a large silk mill complex in Catasauqua. In an oral history interview in 2002, Catherine recounted that her parents let her and her sisters work there in the summers while they were in school and then full time after graduation because they could come home for lunch. “Some of the girls and women in the mill were kind of rough,” she said, “and our parents didn’t want us to spend too much time with them.” This up-bringing stayed with Catherine and her sister June, who worked as a winder at Catoir. They were both kind, soft-spoken, diligent, and hardworking,

Like Irene, Catherine stopped working when her children were young. When she returned to the silk mill in the 1960s, she found that most of the workers were her contemporaries or were older. This was the general pattern of women’s employment in Pennsylvania’s textile industry: they started in their teens and early twenties, moved in and out of mill jobs as their families’ needs changed, and stayed in the mills through their working lives. As a warper—one of the most exacting and mentally demanding jobs in a weaving mill—Catherine’s skill was always in demand, though both the number of mills and the volume of the goods they produced declined steadily beginning in the 1960s.

When Catherine retired in the mid-1980s, my father could not find another local warper, and had to contract the jobs out with a firm in Paterson, New Jersey.

In a way, this completed the circle that started in the 1880s when the first Paterson silk company, Phoenix Silk, expanded operations into Allentown. Paterson had been the center of silk making in the United States for forty years, but improved textile machinery was eliminating the need for many skilled workers. In addition, the Third Wave of immigration brought many experienced silk workers from Austria-Hungary, Italy, and eastern Europe. These new arrivals had ideas about wages, hours, and workers’ rights that challenged the industry’s established order. Faced with labor unrest and a shortage of docile, unskilled workers, the Paterson silk magnates realized that the answer to both problems lay in Pennsylvania, particularly in the anthracite regions.

For the first time, Pennsylvania’s human resources, rather than its natural ones like coal, attracted attention and investment. In the coal regions, thousands of the daughters, children, and unmarried female relatives of miners and railroaders had few opportunities for work. “Throwing” – the process of washing, winding, and twisting raw silk into yarn that could be woven or knitted – was labor-intensive but easy to learn. Paterson’s mill owners soon found themselves being courted by many coal region communities with large young female populations to move their throwing operations west.

In 1887, Weatherly, in Carbon County, won the first big prize: the Read & Lovatt Company. The town of 2500 put up $35,000 of the $50,000 to construct a large mill and get a rail connection to the Lehigh Valley Railroad. Weatherly got its money’s worth: within a year, 225 townspeople worked in the mill, making an average of $1.50 per week. By 1895, Read & Lovett was the largest throwing mill in the world, and 20% of the townspeople worked there, including virtually every female between 13 and 21.

Silk was spun on to 42,000 bobbins everyday at the Read & Lovatt throwing mill in Weatherly

After the US economy finally recovered from the devastating Panic of 1892, the silk industry in Pennsylvania developed rapidly. In 1900, there were 25 silk mills in the Lehigh Valley, most of them weaving broad silks (dress goods) and ribbon. Two Lehigh Valley mills, Bethlehem Silk and Simon Silk in Easton, kept the full manufacturing process in-house, with raw silk coming in and finished goods coming out. Each of these huge operations employed over 1,000 people by 1910. Though there was at least one silk mill in every county in the Commonwealth, the industry was concentrated between the Delaware and the Susquehanna. One-third of all American silk workers were Pennsylvanians and 60% were female.

Historian Bonnie Stepanoff, one of the few scholars who has studied the American silk industry, writes

By a vast margin, Pennsylvania’s early twentieth century silk workers were …unmarried young people, living in the households of their birth and contributing to the family income. These young workers helped to support families headed by coal miners, railroad workers, other male laborers, and their widows. More than 60% of them were female. Most were in their teens or early twenties. Some were eleven or twelve years old, and some were single people in their mid- to late-twenties or older, still living with the families of their birth. (Pennsylvania History, Vol. 59, No. 2, April, 1992.)

In 1911, a huge national study of women and children’s labor found that females over 16 made up three-quarters of the workforce in Pennsylvania’s weaving mills, and sixty percent of the workers in throwing mills. In the latter, another 30 percent of the workers were children. The small percentages of men working in those mills were mechanics (an entirely male domain) and some weavers. Unsurprisingly, the wages paid to the women and children were much lower than the men’s. In 1904, notes Stepenoff, the average annual wage for a male silk mill worker was $485.11, for females, it was $345.44, and children of either gender, working sixty or more hours per week, earned $143.64; she puts these figures in context by writing that the average annual rent paid by the head of a household at that time was $165.00.

In 1913, Pennsylvania surpassed New Jersey (which is to say Paterson), as the largest silk goods producer in the United States; the same year, the United States became the world’s largest producer. This meant that eastern Pennsylvania was the world center of silk manufacturing.

During the roughly two decades that Pennsylvania dominated the world’s trade in silk goods, labor statistics show that the number of people working in the silk industry equaled, and sometimes exceeded, the number working in some of the heavy industries. As child labor was gradually abolished, the average age of silk workers moved into the late teens and early twenties, though women still made up the vast majority of the workforce.

By the late 1920s, the profile of female workers in Pennsylvania’s silk mills had changed to married women and mothers and older unmarried women. The average age of silk workers steadily advanced through the 20th century. At the same time the industry contracted, buffeted by outside economic forces, and failed to attract younger new workers because it remained relatively low-paying and not unionized.

The economic impact of Pennsylvania’s female silk workers has not been well studied, but anecdotally, it was enormous. Their work supported stores, churches, schools and the communities they lived and worked in. Most of the women who worked at Catoir lived in homes that their wages had help buy. Many of their children graduated from college and held white collar jobs. They travelled, and most enjoyed retirement–when they eventually retired.

The women and men at Catoir saw the finished product of what they produced every day, and were proud of it. They were also proud, though a little dismayed, that they were the last of their kind.

Join the Conversation!