Stephen Crane’s Visit to an Anthracite Mine

by NCM Historian Martha Capwell Fox

In 1894, while waiting for McClure’s Magazine decision on whether or not to serialize The Red Badge of Courage, Stephen Crane accepted an assignment from the year-old periodical to visit and write about an anthracite mine near Scranton. Though this was nearly a decade before McClure’s became the cradle of muckraking journalism under Lincoln Steffens, “In the Depths of a Coal Mine” was a graphic indictment of the difficulties, dangers, and stark horrors of work in the anthracite mines and breakers.

Crane’s opening paragraph sets the scene—and tone—of his story.

The breakers squatted upon the hillsides and in the valley like enormous preying monsters, eating of the sunshine, the grass, the green leaves. The smoke from their nostrils had ravaged the air of coolness and fragrance. All that remained of vegetation looked dark, miserable, half-strangled. Along the summit line of the mountain a few unhappy trees were etched upon the imperial blue, incredibly far away from the somber land.

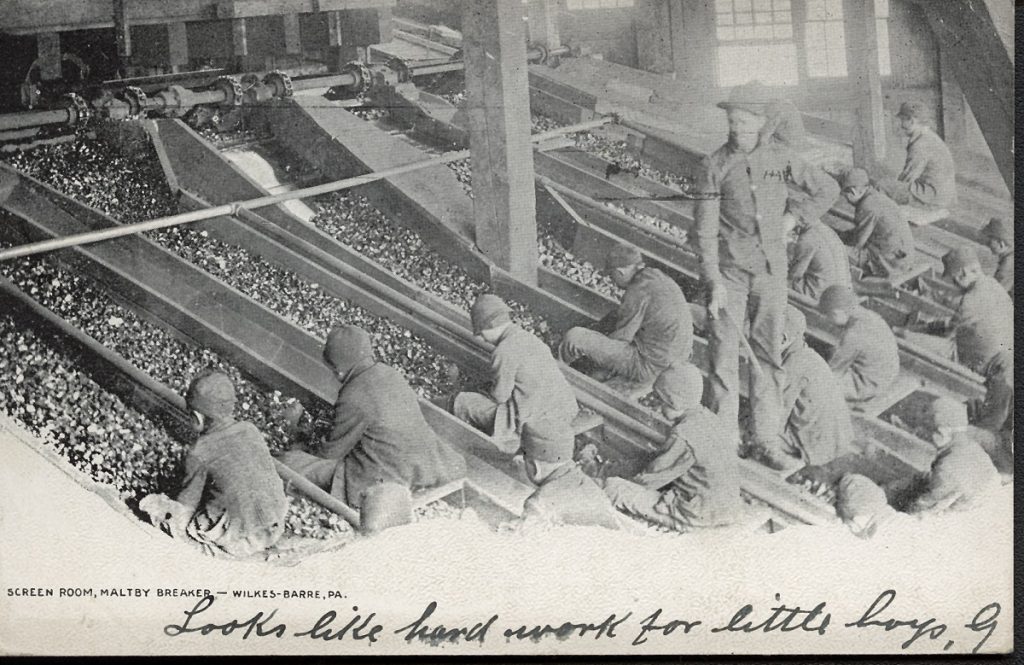

Crane was both impressed and aghast at the breaker boys. He noted that they are so young they are “yet at the spanking period. One continually wonders about their mothers, and if there are any schoolhouses.” These boys work in dirt, dust, and “infernal dins…in the midst of it sit these tiny urchins, where they earn 55 cents a day each. But they are uncowed; they continue to swagger,” swarming Crane and another visitor demanding tobacco as they ignored the foreman’s orders to get back to work.

If the breaker was a monster, the mine was its maw. A guide led Crane through seeming endless miles of tunnels, some so low they were forced to their knees, others vast chambers whose edges were shrouded in darkness beyond the frail light of their miners’ lamps. They passed men crouched almost prone in crevices, drilling and hammering the coal free from the earth, or lying exhausted on the damp stone.

Crane saw no promise in their futures:

If a man escapes the gas, the floods, the squeezes of falling rock, the cars shooting through little tunnels, the precarious elevators, the hundred perils, there usually comes to him an attack of miner’s asthma that slowly racks and shakes him into the grave. Meanwhile, he gets $3 per day, and his laborer $1.25.

In this group photo, the two boys in flat caps are likely breaker boys. The tiny boy at the right, wearing a helmet with a miner’s lamp was probably a door boy – an even harder and more dangerous job than that of a breaker boy.

But people who lived in sunlight and houses warmed by coal were oblivious to this. As the mine elevator lifted Crane into a “downpour of sunbeams” he realized “Of that sinister struggle far below there came no sound, no suggestion save the loaded cars that…went creaking up the incline that their contents might be fed into the mouth of the breaker, imperturbably cruel and insatiate, black emblem of greed, and of the gods of this labor.”

Crane himself fell prey to lung disease, dying of tuberculosis on June 5, 1900 at the age of 28.

Join the Conversation!