Revealing the Black Beauty of Anthracite Coal: Charles Edgar Patience (1906 – 1972)

Written by Martha Capwell-Fox

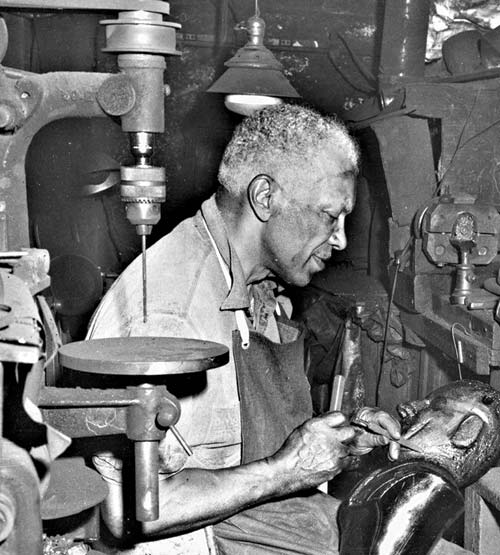

An image of C.E. Patience in his workshop, carving what appears to be a bust. This image originally appeared in Pennsylvania Heritage Magazine Volume XXXVI, Number 1 – Winter 2010.

The son of a formerly enslaved person, Harry B. Patience was born in Pittston, Pennsylvania. He was sent to work as a breaker boy at a very young age and turned the whittling skills he learned from his father towards carving the small bits of anthracite coal he found, a material almost ubiquitous in Luzerne County during the late 19th century. He became so adept at the craft that he and his brother went into business creating jewelry and small objects carved out of coal, selling the pieces from a small store in their house. After a few years, their creations became popular with both the local residents and visitors who wanted to own a beautified piece of the mineral that underlaid their homes and the economic life of the Lackawanna Valley. Harry’s son Kenneth expanded the business further to stores in Philadelphia and New York, and even had an exhibit at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, where he sculpted and sold many miniatures of the Fair’s “Trylon and Perisphere” symbol.

“A heart-shaped pendant carved from anthracite coal is attributed to C. Edgar Patience from a design by his father Harry Brazier Patience.” Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift from Dr. Juanita Patience Moss and descendants.

Kenneth’s brother Charles (1906-1972), who went by his middle name Edgar, shared his family’s fascination with anthracite, but he believed that coal carving could be art rather than craft. He set out to teach himself sculpting, travelling to museums and art galleries, studying books on sculpture technique, and experimenting with ways to work on coal to carve his visions for it. He found that the best anthracite, free of faults and flaws, came from the mines near Hazelton and Tamaqua.

For a time, Edgar supported his family by working in the family business, but his wife Alice believed in his talent, so she took on earning their living and freed him to devote his full time to his art. He built a workshop at their home on Loomis Street in Wilkes-Barre to contain equipment that ranged from strong lifts for moving the large blocks of coal he often worked with, to large and small saws, and very delicate tools for carving. He began exhibiting his work at craft and art shows in the area, but his reputation quickly spread.

Image of an alter at King’s College, one of the most famous C. E. Patience pieces. The base of the alter is carved out of anthracite coal. This image was found on The Citizen’s Voice.

Famously, Congressman Daniel Flood bought numerous pieces of his sculpture and gave them to every president from Franklin Roosevelt to Richard Nixon, as well as to Lady Bird Johnson.

Patience’s work was exhibited in the Smithsonian Institution and the lobby of the United Mine Workers headquarters in Washington, his busts of Washington and Lincoln are part of the Anthracite Heritage Museum’s collection, and he even carved a bulldog for the president of Mack Trucks and the official seal of the island nation of Barbados.

Two of his most prominent works are also the most massive: “Coal Town USA,” a miniature mining town carved out of a huge block of anthracite, with houses, streets, stores, a breaker, coal cars, and miners. Now owned by the State Museum in Harrisburg, this was a seventeen-year work of love that he did in his spare time. The other large sculpture is the 4800-pound anthracite altar in the chapel of Kings College in Wilkes-Barre, with hundreds of polished facets surrounding a cross and a phrase in Latin.

Though he never worked in a mine, Edgar fell prey to the lung diseases that came from working in coal dust. He died after a short bout of pneumonia in 1972 at the age of 65, but his works will forever be remembered as an important part of history.

An image of a C. E. Patience sculpture carved from anthracite coal found in the National Canal Museum archives. On it says “Old Company’s Lehigh” with the name Mr. Oscar Geddes carved on the bottom.

Sources:

- African-Americans in the Wyoming Valley 1778-1990 by Emerson I. Moss

- Bridging Change: A Wyoming Valley Sketchbook by Sally Teller Lottick

- Anthracite Coal Art by Charles Edgar Patience, by Juanita Patience Moss. Willow Bend Books, 2006.

**Brought to you by a project made possible in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities. The views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this post do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.**

Join the Conversation!