Finding the Black canallers of the Anthracite region

Written by Dr. Rachel Lewis, Diversity Research Historian

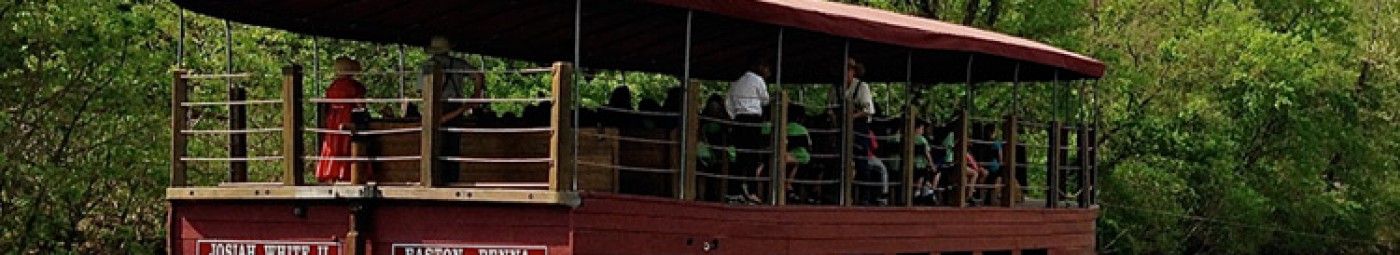

The National Canal Museum has embarked on an effort to make the stories that we collect and share more fully representative of the history of our region. As part of that effort, we are working to better understand and preserve the history of Black canal workers in the Anthracite region.

Q: Now, how many black people were on the canal that you know? Quite a few in this area?

A: There was quite a few, but I can’t remember their names. Mary Taylor and Joe Taylor, they lived here. And Mr. Haines lived here. There were a lot of men that lived here — all the way up to the end of the street, but I can’t remember them now.

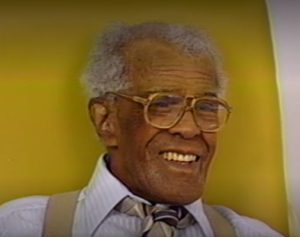

Florence Van Horn, daughter of Morris canal boat captain James Campbell. Image circa 1975 from Tales the Boatman Told.

This exchange happened on September 15, 1975, when James Lee interviewed Florence Van Horn for Tales the Boatman Told. Her father, Captain James Campbell, boated on the Morris Canal. Campbell is one of the few Black canallers who is widely remembered, at least among those who know canal history.

As Mrs. Van Horn put it so well, we know that there were quite a few Black canal workers, but we did not know their names or their stories. Our Diversity Research Historian, Dr. Rachel Lewis; Summer Research Intern, Hannah Pfiefer; and our Inventory Coordinator, Wendi Blewett, have been working together to find records of Black Canallers. Using US census records, oral histories, and collaborating with fellow historians, as of July 2022 we have been able to identify 174 individual Black canal workers. These include captains, boatmen, mule tenders, locktenders, and other related workers. This is a fantastic improvement from where we started. Prior to this deep dive research, we knew of only one Black canaller along the D&L, 4 on the Morris Canal, and after collaborating with the historian at the D&H Canal Museum in High Falls, New York, another dozen or so.

The individuals we did know about before 2022 were a rarity. Most were known because of the documentation that was sought long after the canals closed. An example is Captain Jimmy Brown. He was one of the very last D&L boat captains. In the 1980s and 1990s, when the NCM started doing oral histories with the surviving canallers, he was interviewed. Brown was 81 at the time of his first interview.

Captain Jimmy Brown in December of 1991 during his oral history interview. He is 91 years old.

Captain James Campbell is another Black canaller whose story was saved. His family has worked hard to preserve his legacy. As well as the interview with his daughter Florence mentioned above, he is also named in the poem Famous Tiller Sharks, though referred to as Captain “Camel” in the poem. Of the thousands of people who worked on canals around the Anthracite region, very few got this kind of historical treatment.

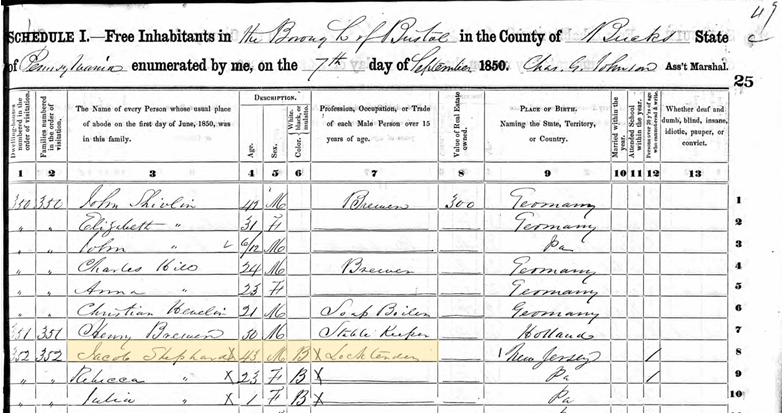

Finding more names requires some fascinating, if at times tedious, research. Most of the names came from searching digitized US census records. Using Ancestry.com we were able to search within the counties that the canals ran through for people who are listed as “Black,” “boatmen,” or “locktender.” This gave us some of our earliest additions to our list of known Black canal workers. Once towns with Black canallers were identified, we could go line by line within those records to find others. The search function on Ancestry.com is imperfect and we wanted to be sure we got everyone we could.

Using a list compiled by historian Bill Merchant at the D&L Canal Museum we were able to use those names to get a toe hold in the communities along the D&H. Merchant identified people through newspaper articles, locktender logs, and reading the transcript of the 1872 court case, D&H v. PA Coal.

1850 census record for Locktender Jacob Shephard.

What are the challenges of this project?

The largest issue is a lack of documents. What few employee records that were made are mostly lost and the majority of those who boated on the canals had no formal relationship with the canal companies anyway. Compounding the problem is that regular folk just do not produce as much documentation and what they do produce is often not saved. We chose to look at census records because, theoretically, every person in the county is counted listing their name, race, and occupation. We were able to get quite a few names using this approach. The problem with the census is that it is only every 10 years and canal work was very fluid (sorry for the pun). Someone might work on the canals for a few years, but if not during a census year that person would not be documented. Canal work was also mobile and so the census, which is taken in the summer, might not catch everyone on the canal.

There is also a 20-year gap in the census record at the end of the 19th century, a critical time for our research. Most of the 1890 census’ population schedules, where individual names and occupations are recorded, were severely damaged by a fire in the Commerce Department Building in January 1921. The loss of the 1890 census means that even more Black canal workers slipped through our already rather porous dragnet.

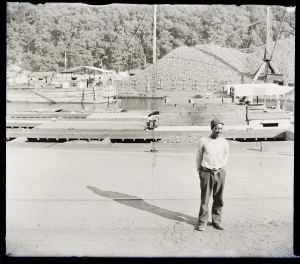

Jim Jackson was a “shoveler” on the Delaware and Hudson canal. We do not have a census record for him. This image is circa 1895 and is curtesy of the Delaware and Hudson Canal Historical Society #83.01.13.

Within the census record, we have another issue: how a person’s occupation is listed. With “boatman,” “captain,” and “locktender” in towns along the canals we can be very sure they were working on the canals as well. Some census takers even bless us with a clarifying “on the canal” in the occupation section. “Laborer,” however is much harder to pin down. It was a common occupation all over the US, not just in towns where people worked loading and unloading canal boats. Some laborers surely were working on the docks, but without notes of where they labored or some other bit of additional evidence, we cannot assume that they worked on the canals.

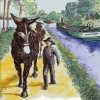

We have a similar issue with female canal workers. Of our named Black canal workers, only 3 are women. Only one of them we found in the census record. We know that many of the locks and canal boats were operated by families, especially in the later part of the canals’ operation. That means that women and girls were working alongside and doing the same kind of work their male counter parts were doing. The contributions that they made to the operation of canal boats and locks were rarely documented. Their work is mostly acknowledged in oral histories and reminiscences, not in official records. Within the census they may be listed as “at home”, “keeping house”, “at school” or simply do not have an occupation listed at all. That does not, however, bar them from also working on the boats, walking with the mules, or operating the locks. This type of informal labor makes it difficult to accurately count, let alone name, those women and girls who might have worked on the canals.

Though we will never be able to name all the Black canal workers there ever were, with our research, the help of descendants, and collaboration with other historical organizations we will continue to find and name those who have been overlooked for decades.

Captain James Campbell’s boat and crew on the Morris Canal on October 17, 1905. Image from The Morris Canal: A Photographic History by James Lee, 1979.

**Brought to you by a project made possible in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities. The views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this post do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.**

Join the Conversation!