George Harvan beyond the Coal Region

Written by DLNHC Intern Mally Diaz-Morales & DLNHC Collections Manager Wendi Blewett

Harvan. The Amish Collection, mentioned below. This is one of the few photos we’ve found in color.

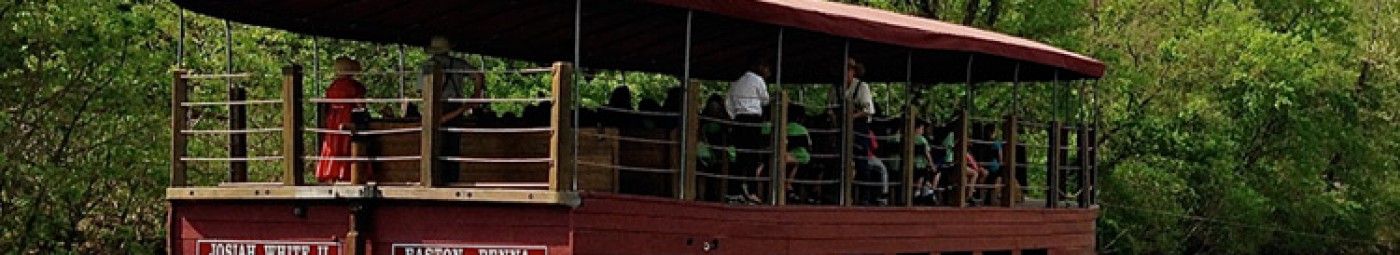

George Harvan is well-known for his black-and-white photos of coal mining in the Pennsylvania Anthracite Region. These photos depict the miners as they worked, toiling away deep down in the earth, and as they lived. Their bright smiles, vibrant spirits, and tenacity shine through every picture. Harvan is remembered as a freelance and newspaper photographer through his work at Lehigh Coal & Navigation, Bethlehem Steel, and The Valley Gazette. His work has been displayed nationally, and works from his coal mining collection are currently displayed at the National Canal Museum’s exhibition, Coal Country Portraits.

Yet Harvan’s body of work contains collections that are far different from the mining series he is famous for. They are vast in number and incredibly diverse. As with the mining series, he photographed in black and white, although there are some collections with color. Harvan also experimented with film. He printed pictures, cut them up, and reassembled them. He manipulated the emulsion on Polaroids to give the image an impressionistic feel. His work is gritty and real. He presented life as it was.

Harvan. The Japan Collection.

The Japan Collection

George Harvan’s first introduction to professional photography began post-World War II. While he was in the Army, he was known to enjoy taking pictures. Once the war ended, his captain offered him the opportunity to travel to Japan with the Special Services.

In late 1945, he ended up in Japan and became a photographer, even though he had no formal training! He spent his free time travelling around and photographing people on the street. In a series of interviews for Tom Dublin, Harvan discussed his experience in Japan. He said to Tom, “I think that was the beginning of my serious photographic endeavors. I felt then that this was what I wanted to do with my life, to be a photographer” (Harvan, Third Interview).

After the Fire

When he returned home in 1947, he applied for a job at the Morning Call newspaper to be a photographer. He continued to work as a freelance photographer throughout the 1950s, selling his work to magazines like Photography, Modern Photography, and Look and Life. In the early 1960s, he began photographing rock faces along the Lehigh River. These photos would become the collection “After the Fire,” named because Harvan believed that “this is what Earth would look like if civilization was demolished and only the images remained on these frozen rocks” (Harvan, Third Interview).

The Amish

For his next collection, he turned to photographing the Amish in Lancaster, PA. While photographing them, Harvan took care to respect their privacy. He would photograph them from afar or with concealed cameras to avoid intruding on their lives.

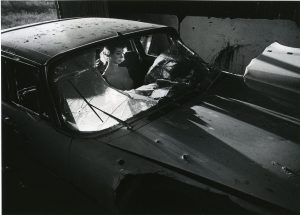

Harvan. The Mannequin Collection.

The Mannequin Project

Another project from the 1960s involved using a mannequin Harvan found while on a walk in Lansford. The mannequin, propped up in an old car, turned out to be a wonderful shot, so he returned to the spot only to find the mannequin gone. A brief look around revealed the mannequin in a new spot and with new damage, so he took photos of that. He would go back periodically over the course of the next year and either find or move the mannequin. The photos show the mannequin in a different place, form, and state of deterioration.

To him, the mannequin was the perfect representation of the human condition, to age and deteriorate over time.

Civil War Battlefields

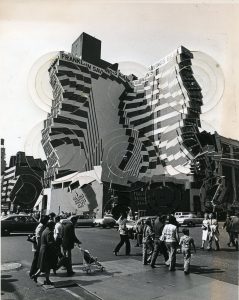

The New York Collection.

For his series on Civil War battlefield statues, Harvan would manipulate the camera to give the figures movement and life. He would move the camera, take it out of focus, or use a zoom lens to get images with more emotion. This collection includes monuments from Gettysburg, Antietam, and Charlottesville.

Many of his projects lasted years. It was important to Harvan that his collections have depth and meaning. He looked for humanity in every photo he took. For example, a series on county auctions held by the Pennsylvania Dutch focused on the faces of people attending and the relationships with others around them.

His New York series focused on the fast-paced lives of people he encountered on trips to New York City to sell photographs to magazines. To get truly candid photos, he would keep his camera hidden or down by his hip. (See Right: Harvan’s manipulation of these photos gives the landscape a futuristic feel.)

Harvan’s works are now held in the archival collections of the National Canal Museum. He left these materials to us, and we are honored to preserve them for generations to come. To see some of the mining portraits he was known for, visit our Coal Country Portraits exhibition, open now until December 2023!

Sources

Harvan, George. “The Oral History.” https://www.albany.edu/jmmh/vol3/harvan/interview/interview.htm

Harvan, George. “Third Interview, June 18, 1997: Work in Japan, Returning to the Anthracite Region, and Photographic Career, 1946-1997.” https://www.albany.edu/jmmh/vol3/harvan/interview/harv3.htm

Join the Conversation!