The Last Underground Miners in the Panther Valley

Written by Martha Capwell Fox, DLNHC Historian

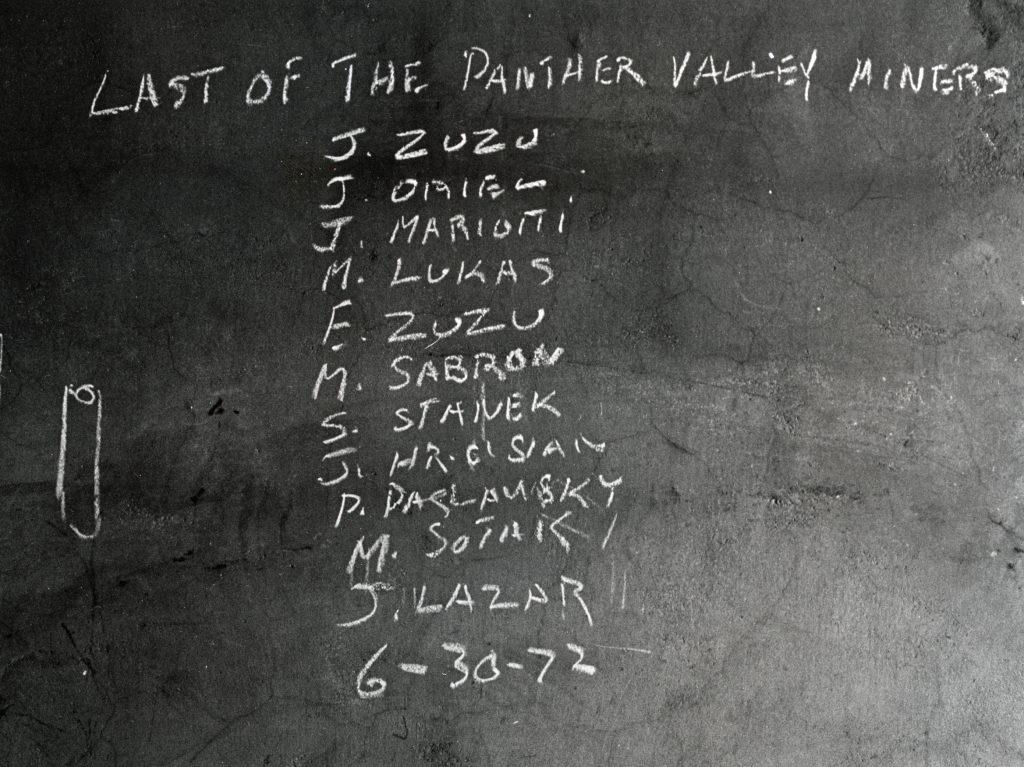

The names of last Lanscoal miners were chalked on the wall of the wash shanty.

Sixty years ago this month, the last deep anthracite mine in Carbon County’s Panther Valley shut down.

Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company opened its No.9 mine in the north face of a hill between Lansford and Coaldale in 1855. For the next 117 years, miners hacked and blasted black diamonds from the Mammoth Vein, the largest deposit of anthracite coal on earth. No. 9 was the longest continuously operating coal mine in the world.

By the early 1950s, that long run was threatened. Demand for anthracite declined after World War II, miners lost workdays, and their productivity went down. The costs of keeping low-output mines open began to drain money from other profitable parts of the corporation. All the Lehigh Navigation Coal Company’s Panther Valley mines—Nesquehoning, Lansford, Coaldale, and Tamaqua—were temporarily closed on May 3, 1954, while the company and the United Mine Workers union worked out a deal to increase productivity.

The miners balked at the new work rules. Defying union orders, they picketed the mines to keep them from reopening. As losses mounted, the company shut down mine operations permanently on June 30, 1954. With their jobs gone, most of the miners went far afield for work.

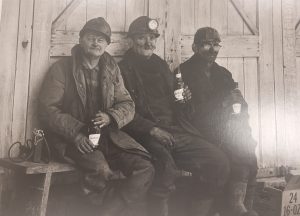

“Everybody went to Bethlehem Steel, and Mack Truck, and different places -Fairless Steel and Linden (New Jersey),” miner Mike Sabron told Professor Thomas Dublin in an oral history in 1993. “They didn’t want to go away. They’d come home over the weekend, and we used to drink a lot.”

Mike Sabron (left) and the Palowski brothers wash down the dust after a day’s work. “In the morning and after we come out we always had a box of beer there waiting for us,” said Sabron.

Two small coal companies leased parts of the closed mines and called back some of the miners. But only the Coaldale Mining Company, which took over No. 8 and No.9 mines managed to survive until 1960. When it shut down, twenty-two of the miners, including Mike Sabron, formed a cooperative called Lanscoal Company and leased No. 9 mine.

For twelve years, this small band of miner brothers kept their jobs and traditions going. It was harder work than usual because they had to do everything themselves, without the loaders, motormen, and outside workers they had been used to. “You’d have to make the timber [roof supports] and lug it up,” Mike Sabron remembered. Each miner was paid the same, about eighteen dollars a day.

By 1970, age, black lung disease, and stringent new safety and environmental rules all took their toll on Lanscoal. “There was enough coal there to mine,” said Sabron, “but they wanted us to put new trolley lines in and drive a chute out for air. We started out with twenty-one of us and we ended up with ten when the mine closed.”

Photographer George Harvan recounted the poignant story of June 22, 1972, the last day of 150 years of underground mining in the Panther Valley.

Mike Sabron waves from atop the last car of coal mined in Panther Valley, June 22, 1972. The downpour of Hurricane Agnes is clearly visible.

Operations at the mine on that final day were to be brief and simple. A string of coal cars was to be loaded with anthracite at the chutes and brought outside…Fate intervened, however, and at mid-morning Hurricane Agnes struck with a vengeance. Lanscoal refused to die graciously. It had long served an important purpose and seemed not about to give up without a struggle.

Heavy, relentless rain made it impossible for the miners to prevent water from quickly reaching dangerous depths in the gangways…water and mud obliterated the tracks leading from the mine…rails broke loose from the roadbed, causing the slowly moving cars to derail time after time. Getting the final “trip” of anthracite to the outside became the last major challenge for the Lanscoal miners.

As the day wore on, the miners were soaked to the bone, but continued to work in water that rose above their knees. Finally, the trip of coal cars, reduced to just two, reached their final destination—daylight. A large sign on the rear car read “Last Car of Coal Mined in the Panther Valley,” vividly portraying the final chapter of the valley fabled deep coal mining industry.

Sixteen of George Harvan’s photographs of the Lanscoal miners are part of the National Canal Museum’s current exhibit, Coal Country Portraits.

For further reading: When the Mines Closed: Stories of Struggles in Hard Times by Thomas Dublin, photographs by George Harvan. Cornell University Press, 1998.

Coal Miners of Panther Valley Photography by George Harvan, Text by George Harvan, Thomas Dublin and Ricardo Viera. Canal History and Technology Press, 1998

Join the Conversation!