Winters on (or off) the Canal

Written by Cyan Fink, DLNHC Inventory Coordinator

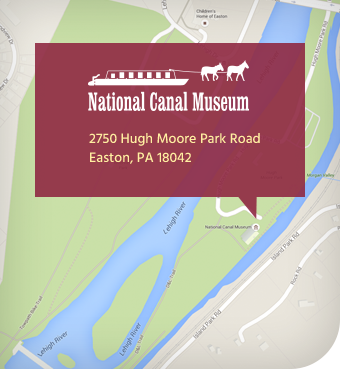

At the end of October, The National Canal Museum will put Josiah White II to bed for the winter. Tim Cramer, our Facilities & Infrastructure Manager, will winterize the boat and the city of Easton will start to drain the canal causing the boat to settle on concrete piers. Josiah will stay there until the spring when Tim inspects it and prepares it for next season.

Our yearly winterization process isn’t much different from the off season for the canal boatman back in the day. Their seasons were a little longer, typically lasting until December before ice started to form and work needed to be halted. The boats would be pulled as close to the boatman’s home as possible. Sometimes if the ice developed quickly and boats got stuck, a scow would have to go up the canal to break the ice so the boatman could make it home. On the Erie Canal, boats were stored in deeper basins, where the water was less likely to freeze. On the Delaware and Lehigh Canals, the boats could be stored in the middle of the canal where the water was deeper and less likely to freeze. When the canals were drained, the boats would settle on the clay mud underneath. If boaters were lucky enough to live near a boatyard, they could also store their boats there.

Lock 13 of D&R in winter. View from east.

A newspaper article from the December 22, 1897, issue of the Allentown Democrat stated that Lehigh Canal had closed for the season, as the last boat, Alexander P. Gest, captained by Otto W. Pursell had left Coalport for Woodbury, New Jersey. The article claims the 1897 season had, “continued for nine months without interruption, which was something unusual, it nearly always being necessary to help the last boats down with an ice machine.”

Many boatmen and their families had private houses or family they could stay with along the canal. Young children would attend school and older members of the family might get temporary work at a mill, furnace, or other local industries. They could also work on the canal, but in a different way. Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company would drain the canal for any necessary maintenance. This was the perfect time for work and reconstruction to take place, as it would not interfere with the flow of boat traffic. In an article from 1911 in the Morning Call reported that the Erie canal had closed, and water was drawn off for work on locks 23, 24, 25, and 26. Sometimes it was not the locks that needed repair, but the canal walls themselves. The walls were packed with clay which was easy for animals to dug into, such as muskrats. Any holes caused by animals or weather needed to be filled in or it could cause more damage later.

When March came around and the temperatures began to warm, families would prepare for boat season. Any maintenance caused by the winter weather needed to be addressed before the boats could start their journeys. Once the boats were in tip-top shape and the ice was clear, the canals would be refilled, and the shipping season could start back up.

Join the Conversation!