The Story behind a Signature and a Passport Mystery

Written by Martha Capwell Fox

There is a cryptic inscription on the photograph of Winston Churchill in the National Canal Museum’s current exhibition “To My Most Esteemed Friend: The Autographed Portrait Collection of Charles M. Schwab.” Barely visible near the bottom of the photo it reads: “Winston S. Churchill Souvenir of November 1914.” Unlike almost all the autographed photos in Schwab’s collection, this one does not mention his name.

Why?

Probably because Schwab was not supposed to be in London, meeting with the First Lord of the Admiralty of the Royal Navy in November 1914.

Schwab received a secret invitation from the Admiralty on October 20. Surmising that the Royal Navy wanted to order munitions from Bethlehem Steel (which would have violated US neutrality in the First World War), Schwab summoned Bethlehem Steel Vice President Archibald Johnston to New York with orders to tell no one where he was going. They sailed for Britain in the early hours of October 21.

It was easy to make a last-minute booking on the S.S. Olympic. The German Navy had announced that they intended to sink her on sight, so most passengers cancelled their tickets. Six days out of New York, pursued by four German U-boats, Olympic answered a distress call from the Royal Navy ship Audacious that had struck a mine. Olympic rescued the crew and attempted to tow the crippled ship to a naval base in Northern Ireland. But the U-boats sank Audacious and the Royal Navy—hoping to hide the loss of its ship from the British public– ordered Olympic to dock in the naval base, where all the passengers were held incommunicado for a few days.

Schwab, however, was whisked in secrecy to London. Once there (Johnston arrived a few days later) Schwab learned from Admiral of the Home Fleet John Jellicoe, War Secretary Lord Kitchener, and Churchill that the British wanted more than ammunition and guns. They also wanted twenty submarines – quickly.

With his usual optimistic dynamism, Schwab cabled Bethlehem Steel’s vice-president for shipbuilding, H.S. Snyder on Nov.2. Snyder replied on November 3 that twenty subs could be built in the company’s two shipyards in Massachusetts and San Francisco, with engines supplied by the Steel’s subcontractor, Electric Boat Company. In addition, he had already ordered the steel, which was delivered to the shipyards in record time – ten days. Schwab boldly guaranteed the British delivery of ten subs in six months, less than half the usual time, and offered to take a financial penalty if the deadline was not met. The Royal Navy men were overjoyed; First Sea Lord John Fisher wrote to Jellicoe “It’s a gigantic deal done in five minutes! That’s what I call war!”

Schwab and Johnston arrived back in New York on November 20 with the British Treasury’s advance payment of $15 million. News of their top-secret trip leaked out, and Schwab, Johnston, and Snyder were ordered to meet with President Wilson and Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan on December 2. They expected to be told to break the contract, which violated US neutrality by shipping weapons to one side in a war. Instead, Bryan told them that Wilson did not object to Bethlehem building the submarines, just shipping them to Britain.

The Steel men and the engine builders met in New York the next day. It is unclear who came up with the idea of making the parts in the US and having the submarines assembled in and shipped from Canada, though it is often attributed to Johnston. On December 3, Schwab travelled to Montreal to inspect a shipyard in Montreal owned by the British firm Vickers; he was impressed but no one on site was authorized to negotiate with him.

On December 5, Schwab and Johnston boarded the Lusitania and headed back to Britain to meet with Vickers’ officials. They arrived on December 13 and paid what they thought was to be a quick courtesy call on Churchill and Fisher. Instead, Churchill angrily attacked Schwab, saying he had deceived them by making a contract he could not fulfill. He accused Schwab and Johnston of treachery and fraud for taking the up-front payment. Churchill refused to allow Schwab to reply until Fisher intervened and said “Schwab, what have you got to say?” The Royal Navy men were astonished to be told that all that was needed was to meet with the Vickers owners to seal the deal to use the Canadian shipyard. Fisher immediately replied that he would personally manage the agreement with Vickers. Schwab and Johnston sailed home on the Adriatic, arriving home in time for Christmas.

By the summer of 1915, ten submarines built in Montreal were in service.

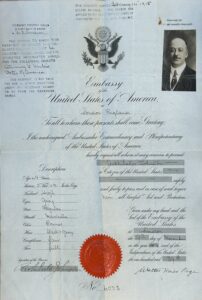

There is another minor mystery associated with these events. Why did Archibald Johnston need this special emergency passport issued by the American ambassador in London so he could get back home? He had made many foreign business trips before; perhaps in his haste to join Schwab in New York on October 20, he forgot to pack his passport? Maybe he didn’t find out he was leaving the country until he got to New York?

The passport is on parchment and is 11.5” x 17”, which must have been inconvenient to carry. One of the unique treasures in our collection, it shows signs of being folded many times. Fortunately, it was in force long enough for Johnston to make two round trips across the Atlantic in two months.

Join the Conversation!