James Blakslee’s Voyage on Pennsylvania’s Canals

Written by Martha Capwell Fox, DLNHC Historian

On April 1st, 1833, James Irwin Blakslee, recently turned 18 years old, set off from his family home in Springville, Susquehanna County, “with all I had in the world tied in a pocket handkerchief, afoot and alone on my way to Mauch Chunk, having hired out to Asa Packer to run a boat at 14 dollars per month and board. I arrived here on April 3rd.”

After two weeks helping Packer, his brother-in-law, build a railroad track to bring coal down from Nesquehoning, young James set off on his first canal boat trip. It must have gone well, because he wrote in a brief memoir in the 1870s that he boated until the season ended in December.

James boated again for Packer in 1834. That season ended in a harrowing late November voyage from New York with a ten-ton load of “store goods” ordered for the Packer brothers’ store in Mauch Chunk.

A Memoir Preserved Through Generations

James Blakslee’s account of his breakneck journey over a series of canals and rivers that were on the verge of freezing is told in his handwritten memoir and a typed copy passed down through generations of his family. The typed version belongs to his great-great grandson, Norman Scarpulla.

Mr. Scarpulla intended to present James Blakslee’s memoir as a paper for the Canal History and Technology Symposium that was held annually from 1982 to 2012. A 2013 meeting was planned but postponed and never rescheduled. His finished paper languished in the National Canal Museum’s files, and sometimes during our occasional email exchanges, he has politely asked if his great-great grandfather’s story would ever be published.

Here it is.

The Harrowing November Voyage

Mr. Scarpulla wrote “This short narrative is a fascinating document concerning canal transportation in the 1830s from the viewpoint of the boat operator.” There are several accounts of early canal travel, but they were written by boat passengers. James Blakslee’s story is unique because it is told by the man in charge of the boat.

Mr. Scarpulla knew that James Blakslee was writing for his family who were quite familiar with the workings of the still-active anthracite canals network. So, his paper includes several clarifications for 21st century readers as well as some plausible explanations for details that James Blakslee failed to include. His comments and mine appear after Blakslee’s tale.

The comments in brackets are mine; the letters in parentheses are from the typed transcript.

On November 20th, 1834, Robert W. Packer [brother and business partner of Asa Packer] purchased in New York about 10 tons of store goods for Packer, Hillman & Co. I assisted in loading them on a steamboat and went with them to New Brunswick, [the eastern end of the Delaware & Raritan Canal, which connects Raritan Bay and the Delaware River] where we arrived in the evening. The next morning I loaded them in a scow boat [a short, shallow-sided work boat with a flat bottom, square bow and stern, and short rudder] and got my bill of lading [a list of the cargo and toll charges] made out, which the collector told me was the first one that had been made for a canal boat loaded with merchandise through the Delaware and Raritan Canal, as previous to that time such goods had all been transported in barges and sloops. (W)e left New Brunswick about noon on Friday and arrived at Bordentown on Saturday about 10AM, too late for the tow boat of that day, and I knew it would not come back until the following Monday, then (go) back down on Tuesday. It being so late in the season the fear of freezing up before reaching Mauch Chunk impelled me to pull out into the Delaware (River) and undertake to float down with the tide (then half spent) to Bristol, a distance of about 10 miles. I was entirely unacquainted with the channel of the river, and the fear of running on sand bars or snags, either of which might sink the boat with the goods, caused me much fear and great anxiety long before we reached Bristol. (W)hen we had floated down within about two miles of Bristol, the tide turned and was about to take us up the river again, when fortunately a small sloop loaded with wood took us in tow and landed us safely at the wharf at Bristol before sunset Saturday evening. I went directly to the collector’s office and got my bill of lading and permit over the Delaware Canal (which I could not have got on Sunday) so I was ready to start in the morning. I drove night and day, all that my horse could stand, until I reached Mauch Chunk and ran the boat into the dock at the back of the old store house…The next morning the river was frozen over. (W)e unloaded the goods, and the boat lay in the lock until next spring.

Mr. Scarpulla wrote “This short narrative is a fascinating document concerning canal transportation in the 1830s from the viewpoint of the boat operator.” There are several accounts of early canal travel, but they were written by boat passengers. James Blakslee’s story is unique because it is told by the man in charge of the boat.

Piecing Together the Missing Details

But we wish James had included a few details.

Such as: was the trip from New York City to New Brunswick his first ride on a steamboat, as seems likely? Was he impressed that he sailed 40-plus miles and arrived in New Brunswick the evening of the day he left New York? His horse-drawn scow trip over the Delaware & Raritan Canal [D&R] took 22 hours to traverse the 44 miles from New Brunswick to Bordentown. Who was the “we” on that leg of the trip? Scarpulla suggests that James hired the scow and a horse and driver in New Brunswick and left the man and horse in Bordentown.

The tow boat he missed was the only way to enter the southern terminus of the Delaware Canal at Bristol, the only northbound route to Easton and the connection to the Lehigh Navigation. [The outlet locks and the cable ferry at New Hope and Lambertville connecting the D&R and the Delaware Canal were not built until 1847.]

A Race Against Ice and Time

Afraid of being ice-bound far from home with his cargo, James opted to make a daring, dangerous 10-mile journey down an unfamiliar river in a hard-to-steer scow. But he was in a desperate situation – and 19 years old – so he took his chances. And his luck changed. He was rescued by a small sailing ship that towed him to Bristol, got his permit to travel and bill of lading just in time, and left Bristol the next morning, a Sunday with his cargo on a boat instead of a scow [Mr. Scarpulla speculates it was a Packer-owned boat left in Bristol for him] .

So, James had travelled from New York City to New Brunswick on Thursday, left New Brunswick at noon on Friday, arrived at 10AM in Bordentown on Saturday, and reached Bristol on Saturday evening. But the longest stretch was still ahead: 114 miles of Delaware Canal and Lehigh Navigation to Mauch Chunk, and he still needed to beat the freeze.

The average distance a canal boat could cover in an 18-hour day was about 35 miles. However, Blakslee’s account implies he was alone, without someone on the towpath with the “horse” [mules became the equine of choice by about 1840]. He writes that he drove “night and day” but he must have stopped at intervals because neither horse nor man could have gone that far without rest. We don’t know how long that last leg took, but he outran the ice, probably to the relief and gratitude of the Packer brothers.

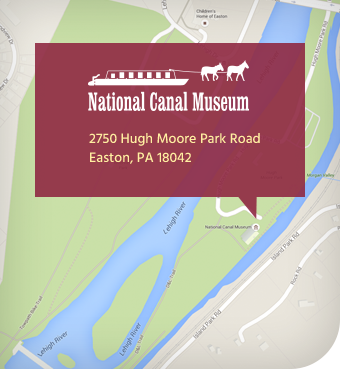

Follow the Route:

Explore the path that we believe James traveled during his daring 1834 canal voyage. View the interactive map here:

From Canal Boatman to Railroad Executive

Blakslee built a long and successful career in the anthracite and railroad industries, driven by his can-do attitude and helped along by his relatives- by-marriage, the Packers. He worked on the construction of the Lehigh Valley Railroad and was the conductor on the first coal train to Easton. He rose to hold executive positions on the railroad and was elected to its board of directors in 1878. He also served as a trustee of Lehigh University. He died in 1901 at the age of 86.

[Mr. Scarpulla lives in Massachusetts, but his Pennsylvania pedigree is impeccable—his great-grandfather, James’ son Asa Packer Blakslee married Louisa Sayre, a granddaughter of William Heysham Sayre, Sr.]

Join the Conversation!