Uncovering the Story of Industrial Women in the D&L Corridor

Written by: Rachel Lewis, D&L Diversity Researcher and Historian

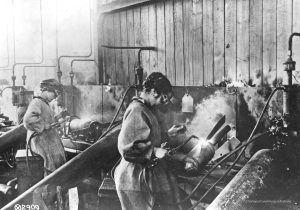

Women welding fins on bombs in 1915.

The history of industrial women in the D&L Corridor is long. Many current residents have female relatives and ancestors who are a part of that history. We know that during the World Wars, thousands of women worked at Bethlehem Steel and other heavy industries while the men went to fight. The story, however, does not stop there. Women worked in industry long before, and long after that. Women worked in silk mills and blouse factories. They made Dixie cups, crayons, car batteries, plastic pipes, cigars, and many other industrial products. For many of these industries, the work force was predominantly women.

The National Canal Museum’s 2022 exhibition, Beyond Rosie and Rivets: Industrial Women in the D&L Corridor tells the stories of the industrial women from our past as well as in our present.

One of the most interesting parts of studying women’s labor history is finding out how deeply interwoven it is with other areas of our industrial history. We know that some industries moved here because there were women to do the work. We also learn that women’s labor helped support their families when a man’s wages could not. After looking closer, we realize that our region’s history is far more complex than we had thought.

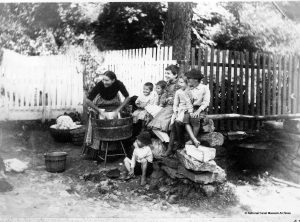

Locktenders’ wives often took in laundry to help support their families.

One consistent thread is that the wages women earned often could be the difference between a family making ends meet or not. In a region where coal, iron, and steel were vulnerable to fluctuating economic conditions, the steady, if low, pay of wives and daughters brought security to the family. For example: the piteous wages that silk workers, mostly young girls, were able to bring home allowed the miners’ strike of 1902 to last as long as it did. This in turn brought national attention to the plight of child workers. Without the income of these girls, some as young as 8, the striking miners would have been starved out.

On the canals, lock tenders were “paid” for their work by living rent-free in the lock house. Their wives and daughters, who took in canallers’ laundry, sold food, and bartered for coal, often while operating the lock as well, brought in the needed cash and fuel to get the family through.

Above right, Katherine Henry operates the pulse-forming and final test set in the Transistor line. In the left foreground below, Catherine O’Shea washed soldered germanium crystals, Delphine Oswald solders the crystals to brass bases, and Elain Starr marks the code number on the 2A. From the Archives, February 1952.

A woman’s wages being her family’s steady income is not just the story of the late ninetieth century. Many of the women who made transistors in the Allentown plant during the 1960s commuted from the coal regions because the declining mining jobs could no longer sustain their families. By then, change was coming. Opportunities to move beyond low paying work and into positions where women could be the primary provider began to emerge. One step towards that was the 1974 Consent Agreement. The agreement required Bethlehem Steel and 8 other steel manufactures around the county to change their discriminatory hiring practices. It gave women access to the well paid and benefited union jobs at the Steel, which once were only open to men.

The work that women of the D&L Corridor did was often dirty, noisy, underpaid, and came with long hours. Those long shifts were then extended after work to the second job of mother and homemaker. At the same time, industrial jobs allowed women to create friendships and networks with other women outside the home. It gave them a sense of independence and belonging and undergirded the family during lean times.

We hope you will visit us to learn more about the fascinating and often over looked history of industrial women in our region.

**Brought to you by a project made possible in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities. The views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this post do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.**

Join the Conversation!