Jewish Heritage in the D&L Corridor

Written by Martha Capwell Fox, D&L Historian & Archives Coordinator

The Easton Experience

Jewish history in the D&L Corridor is interwoven with the broader story of our region. The first Jews in colonial Pennsylvania arrived in Philadelphia in the 1730s, drawn by William Penn’s establishment of tolerance and freedom of worship. They were nearly all Sephardic, the branch of Judaism from Spain and Portugal. Periodic persecution and expulsion of Jews from those countries, which had strong maritime ties to colonies in the New World, drove those Jews first to the Caribbean and then New York, Philadelphia, and the British colonies of Georgia and the Carolinas.

A drawing of of the first synagogue in Easton, which was on 6th St. between Pine and Ferry Sts.

The name of one, Myer Hart, appears on the 1752 list of Easton’s eleven “founding families” that was compiled by William Parsons. Though little is known about his life before then, Hart, described as a “shop-keeper,” appears to have been part of the Sephardic emigration to Philadelphia in the 1740s. Myer Hart and his family lived in Easton for more than 30 years; meanwhile, another 18 men and one woman identified as Jews lived at least for a time in Easton in the 18th century, but never established a Jewish community.

That changed with the rapid increase in German immigration to the US in the 1830s and 40s. Typically, the earliest arrivals were young single men. Easton– the economic hub of the region, the biggest city north of Philadelphia, and largely German-speaking—was attractive. By 1839, enough German Jews had settled together on the hill between what is now 6th and 7th streets to form a community. Congregation Brith Shalom (Covenant of Peace) was founded, the third Jewish congregation in Pennsylvania and the tenth in the US.

Easton’s first synagogue was built on 6th Street between Pine and Ferry Streets in 1842. The presence of Protestant ministers and town officials at the dedication set the tone for the rapid integration of the Jewish community into the civic and economic life of 19th century Easton. The fifty Jewish families prospered as grocers, merchants, clothiers, cattle-dealers, tobacconists, and hotel and saloon keepers. As the 19th century progressed, Easton’s Jewish community provided itself with rabbis, kosher butchers, mohels (trained for circumcising male babies) and other requirements, but at the same time, close observance of many rituals began to decline.

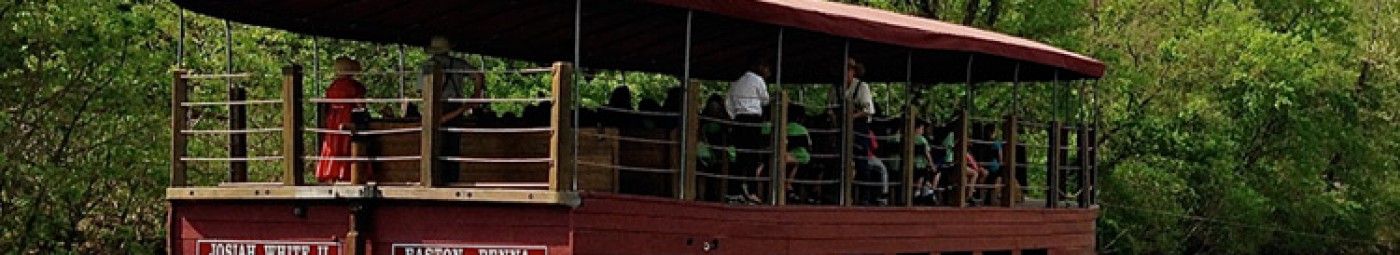

Camptown was a highlight of the summer for the kids of Easton who belonged to the Young Men’s and Women’s Hebrew Association. One big favorite was the excursion on the Delaware Canal aboard a converted scow, pulled by ( of course) a mule. This photo was taken in 1939, but if you recognize your (younger) self or a family member, please let us know!

The “third wave” of immigration between 1880 and 1900 brought a different group of Jews to America. The Ashkenazic Jews were from eastern and central Europe, Russia, and the Baltic countries; they had lived mostly in small, rural, tightly-knit communities where their religious and social lives were enmeshed and embedded in Judaism’s traditional rituals and practices. Their everyday language was Yiddish, so there was a language barrier. According to the history of Easton’s Jewish community by Rabbi Joshua Trachtenberg, the newcomers were not welcomed by their well-established co-religionists, who considered them superstitious bumpkins, while the newcomers regarded Brith Shalom congregants as snobby religious slackers.

Their differences centered on the fact that Congregation Covenant of Peace had evolved into Reform Judaism practices: services in English and less observance of traditional rituals. The Ashkenazim were observant and orthodox. Their need for their own congregation was immediately apparent, and Congregation B’nai Abraham (Children of Abraham) was founded in 1889. Antipathy between the two congregations lasted into the early 20th century, though B’nai Abraham’s 1907 synagogue was dedicated by two Reform rabbis.

But the “Americanization” of the next generation in both groups resulted in their youth members jointly founding the Young Men’s and Women’s Hebrew Association in 1910. In 1915, the group—more social than religious–decided to acquire their own building, and the campaign to raise the money surprisingly brought both congregations, and the businesses their members ran, together. Trachtenberg, writing in 1944, says that this was the first step towards “unity” in Easton’s Jewish community.

Jews in the Wyoming Valley

The first Jews to establish themselves in the Wyoming Valley were probably peddlers—the forerunners of travelling salesmen who brought necessary small wares to scattered farm families. Enough of them had earned enough to settle down in Wilkes-Barre that they established a burial society there in 1843, founded a congregation called B’nai B’rith, and built a synagogue in 1849, the 24th in the U.S. The fund for building was generously subscribed by local Christians, a sign of cooperation and mutual support that has persisted in the community to the present.

These German Jews arrived at a fortuitous time, when Wilkes-Barre and the surrounding Wyoming Valley were in the midst of the economic, industrial, and commercial explosion triggered by the anthracite industry and the railroads. Many became merchants who founded the long-lived prominent retail stores of the region; many were involved in industries like textiles and other manufacturing. This meant that they were not only prosperous, but that they were deeply involved in the growth and governance of their communities.

The reaction of the descendants of the first German Jews to the arrival of Jews from eastern Europe, the Baltics, and Russia was unfortunately similar to that of the original Easton Jews. The fortunate difference was that the newcomers were able to more easily assimilate into the Wyoming Valley’s small towns and coal patches where there were fellow Poles, Lithuanians, Latvians, Hungarians and other immigrants who shared their language, if not their religion. This smoothed the way for many Jewish newcomers to become shopkeepers and even informal bankers for the miners and their families; the situation was helped by the fact that most Jewish immigrants did not go into the mines, so there was no sense that they were competing for miners’ jobs.

The Americanization of the subsequent generations meant that the Wyoming Valley Jews built YM/WHA’s, developed philanthropic associations that were both religious and civic, and became part of the power structure of the region. Though Jews were excluded from some of the high-status clubs and men’s organizations until the late 1950s, by all accounts anti-Semitic incidents were rare; this was also the case in Easton.

May is Jewish Heritage month. Watch for more posts about Judaism’s past and present in the Corridor.

Sources:

Join the Conversation!