Preserving History Post Industry, Anthracite Heritage

Written by Martha Capwell Fox, DLNHC Historian

What happens to a region when the industry that defined its residents’ identity and provided their livelihoods disappears? What do people do when all they are left with are crumbling buildings, sinking ground, abandoned villages, and a blighted, blasted landscape?

When those people are the people of the anthracite, many of them find ways to preserve their local history and their unique culture and memorialize their shared and individual pasts, explains Philip Mosley in a new book, Telling of the Anthracite: A Pennsylvania Posthistory. But he finds a “tension between a need to remember and to forget is a recurrent theme in the posthistory of the anthracite.” Others prefer to forget the past—in some cases because the loss of livelihood and loved ones is too painful—and sometimes in a sense of despair and fatalism. Many people just picked up and moved elsewhere for better opportunities and new lives.

Mosley states in his introduction that he is not a professional historian. He is, in fact, a highly respected scholar of English and European literature, who has written multiple books in his field and translated important Belgian works from French to English. In 1988, he left his native Britain to take a post as a professor at the Scranton campus of Penn State University, where he became interested and then immersed in the culture of the anthracite regions. In part, this grew out of his early fascination with the industrial landscape of his northern England childhood.

When Mosley arrived in Scranton in the 1980s, the final collapse of the anthracite industry was fresh in many people’s lives and memories. Investigations of its demise, which to that point had been largely focused on economic factors, began to spread into various academic fields, including sociology, cultural anthropology, labor history, environmental sciences, ethnic and immigration studies, and the then-growing field of industrial archaeology. This led to increased awareness of the human, economic, and environmental toll that anthracite had taken on the region.

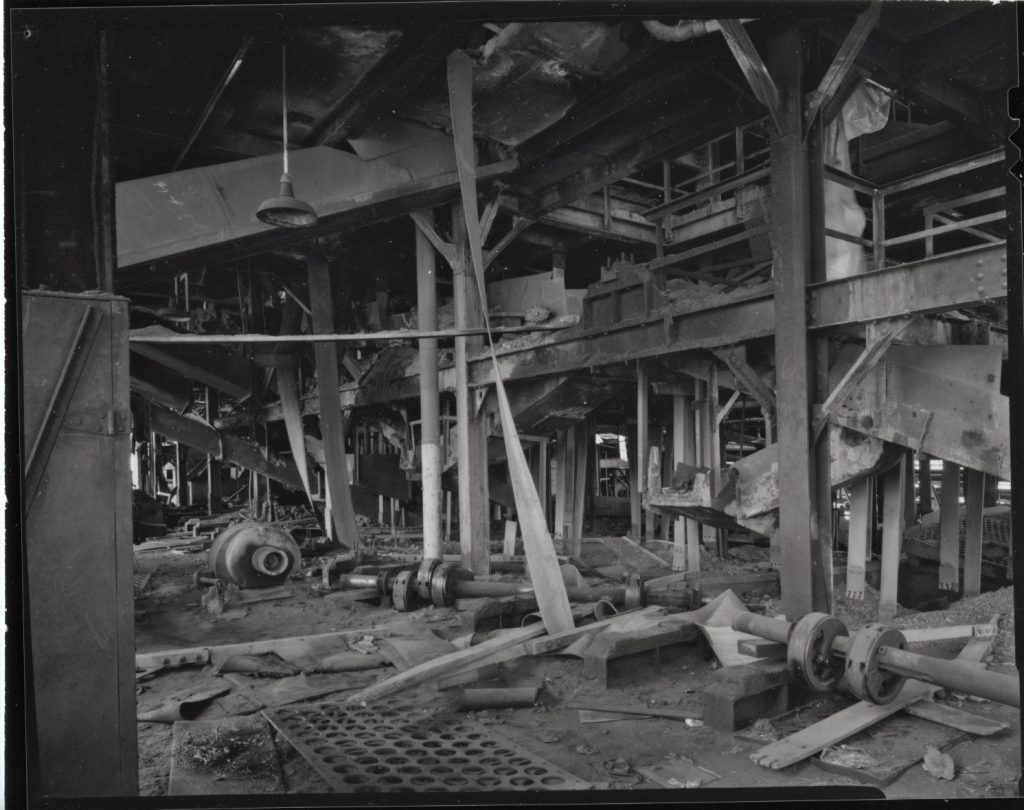

At the same time, local efforts to preserve their heritage—and to use that heritage to construct a new economic paradigm for the region—began to take hold. The material culture of anthracite mining—tools, helmets, miners’ lamps, and other equipment, as well as artifacts of domestic life in coal communities, began to be collected into urban museums and local heritage centers. As the giant breakers that had epitomized the anthracite landscape were demolished, amateur and professional photographers such as Joseph Elliott recorded them in federal programs such as the Historic Architectural and Engineering Record (HAER). On a more local level, memorials of mining disasters like Avondale, and worker massacres such as at Lattimer, many of which had never been memorialized, were installed. Academic and commercial publishers began issuing many books examining various aspects of work and life in the region, joined by amateur and professional theater presentations, poetry readings, and more recently, websites.

Mosley writes that documentary films and television discovered the anthracite region only when the industry was in decline. Company-made documentaries and promotional films had been shot in mines and breakers as far back as the 1920s, but in the 1960s the focus shifted to television investigative journalism. Two of the most notable—The Invisible Man and The Miner’s Story were created by NBC and CBS network affiliates in Philadelphia, and each told a similar story of loss, regret, and an uncertain future for miners, their families, and communities. But Mosley makes only a passing reference to the Sean Connery/Richard Harris movie The Molly Maguires, filming of which gave birth to the renaissance of downtown Jim Thorpe and the state historic park at Eckley, both locations in the film. And he writes disapprovingly at some efforts to present “living history” that plays fast and loose with the facts to attract paying audiences.

Telling of the Anthracite ranges widely over various historic sites, festivals and annual observances, novels, plays, poetry, music (including opera), paintings, and sculpture that have been created in and about the region in the past fifty years. It includes an extensive bibliography, documentary filmography and discography, as well as a gazetteer of anthracite region place names and the coal company they were associated with. But beyond preservation of heritage and culture, Mosley believes that the full history of the anthracite region should be taught in high schools and colleges. Its importance in the industrial and economic history of the United States, the “pride, strength, and loyalty of its people” who were largely immigrants and their descendants, as well as the devastating human, economic, and environmental costs of mining the “black diamonds”, are one of the most important historical lessons for our future.

Telling of the Anthracite: a Pennsylvania Posthistory, by Philip Mosley. Mechanicsburg, PA: Sunbury Press. 2023

Join the Conversation!