The Second Great Awakening and the Sunday Shutdown

Written by Martha Capwell Fox

We don’t know much about the religious practices of the people who worked on the canals in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but we do know that they were caught up in The Second Great Awakening, the fervent religious revival during the 1820s and 30s, because of the hot button issue of the day: work and travel on Sundays.

The Pennsylvania law that forbad everything but worship, prayer, and rest on Sundays dated back to the 1680s. William Penn decreed that a person doing “any worldly employment or business whatsoever on the Lord’s Day, commonly called Sunday” was both a sinner and a criminal. Playing games, hunting, shooting, and any “sport or diversion whatsoever” was also illegal on Sundays.

The Second Great Awakening coincided with the canal mania that was sweeping the eastern US. Flouting a very old law that had been enforced more socially than legally, boats on Pennsylvania’s canals started carrying coal and other freight around the clock and seven days a week (One exception was the Delaware & Hudson Canal, which never operated on Sunday). This flagrant violation of the ban on commercial activity on Sundays was apparently overlooked by the authorities but sparked outrage in many pious people and religious groups.

The Philadelphia Sabbath Association was one of the many organizations determined to restore the sanctity of Sunday. Formed in 1840 by clergy and members of several Protestant sects, the Association set out to stop any kind of transportation – water, rail, even streetcar – on Sundays. Their larger aim was to convert boatmen and mule boys from the evils common on the canals – fighting, stealing, cheating, drinking, and swearing – by sending out missionaries to the canals to preach and teach Bible study.

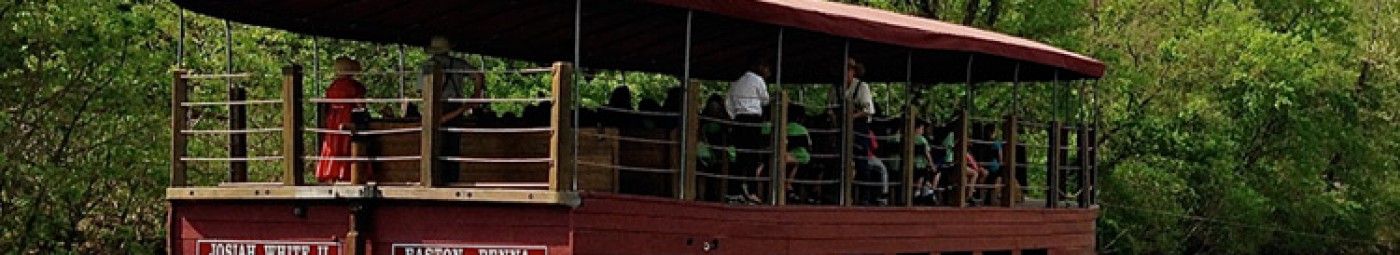

By 1846, the Association had five “laborers” in the field. The energetic Rev. William Hance reported that he had visited “nearly all the principal canals within the State.” He was particularly gratified that ending Sunday navigation on the Lehigh and Delaware Canals had borne fruit. He wrote to the Association’s directors that during his first years of preaching and handing out tracts and Bibles, he had seen little improvement in canallers’ behavior and speech, but by 1847, having a day of rest had led to “a gradual improvement in morals, and the pious Christian is now found on a number of boats.”

Whether it was Hance’s preaching or having a day off, William Zane, the superintendent of the Lehigh Navigation, agreed that the move had been the right one in more ways than one. In a letter to Hance in December 1846, Zane wrote “I have heard of no disorder worth mentioning at the places where they rested on the Sabbath…. Having rested one day in seven…the boatmen have been able to pursue with more energy their calling during the week, and as might have been expected, there has been a marked increase of business on the canal.”

The locktenders had been pressing the Board of Canal Commissioners to end overnight boating for several years. They were the key and an easier group for the missionaries to persuade to close navigation on Sundays. The regulation was not uniformly applied throughout the state, but in general, all the canals were closed on Sundays by about 1853.

Several missionary reports to the Sabbath Association mention holding services in locktenders’ houses and mule barns, particularly on the Juniata and Northern Divisions. After the Sunday boating ban went into effect, some reported that groups of boatmen on the central Pennsylvania canal divisions would tie up on Saturday nights at towns where they were welcome at local churches on Sundays.

The Sabbath Association’s endeavors eventually led to the establishment of at least one new church near the Lehigh Navigation. In June 1847 Rev. Hance visited the canal boats gathered for a Sunday in a boat basin west of Monocacy Creek in Bethlehem. With support from the Moravian congregation, he started a Sunday School near the canal. In October,1851, afternoon services for the canallers began to be held in a storeroom in the Knauss and Borhek lumber yard. A few months later, a Sunday School for neglected children—most likely including mule boys, who were often orphans—opened, but for only a short time.

In 1856, the Sunday School reopened in a nearby schoolhouse and in 1859, three students training for the ministry at the Moravian Seminary began holding prayer meetings for the boat crews there as well. In 1860, the seminarians then opened the West Side Moravian Sunday School and expanded their mission to include residents of the fast-growing neighborhood. Later that year, the West Side Moravian Church was founded and is still active in Bethlehem.

Join the Conversation!