(above, l-r) A woman with a cart holding all her belongings stood in front of the damaged central railroad station; A woman and children leave a library or bookstore that survived the bombing. Most of the dwellings and stores in wartime Tokyo were wooden; Newspapers were a major source of information in post-war Tokyo. These men are reading pages posted outside a newspaper office.

George Harvan’s Journey From Japan to PA Coal Mines

On August 14, 1945, Japan’s Emperor Hirohito announced his country’s surrender, ending World War II. His radio address to his shocked and devastated nation was the first time most Japanese people heard his voice.

Four months later, George Harvan, a 24-year-old son of a Lansford coal miner, arrived in Japan. A soldier in the Army of the Occupation at Johnson Air Force Base near Tokyo, he was put in charge of a photo lab, processing aerial photos and taking pictures of visiting dignitaries for the Army. He was given a Speed Graphic camera, a Jeep, and access to much of the country.

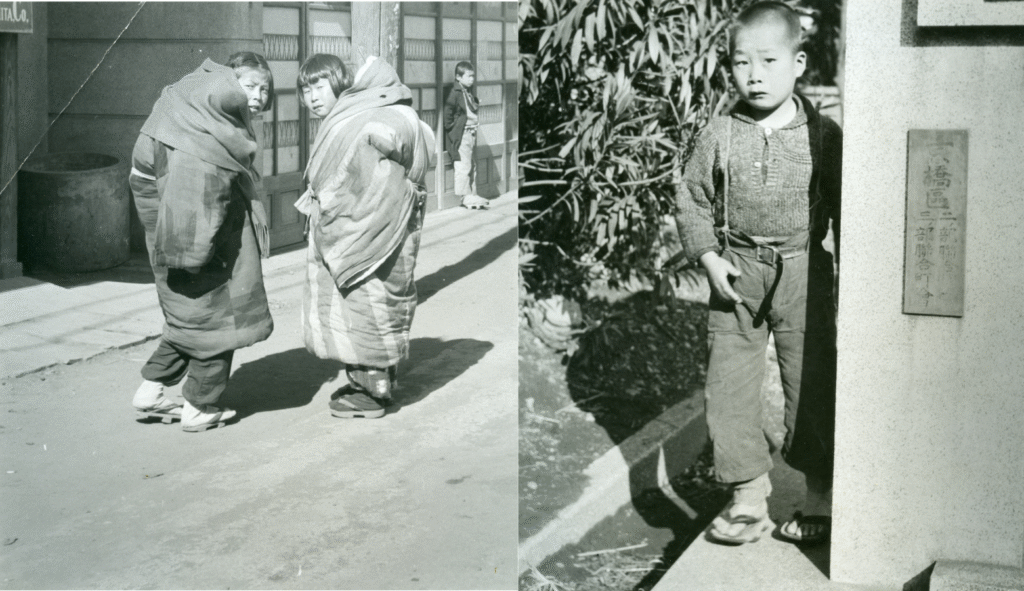

Harvan wrote that these two girls and this boy may have been among the many homeless orphans he saw in Tokyo.

Harvan had never been more than an amateur picture taker. The images he shot in his spare time during his eighteen months in Japan made him a photographer.

In 1947, Harvan wrote that the aim of his personal photography was to see and show the Japanese people as they saw themselves, not as they behaved around American military members. “I strived to portray the feeling…and suffering of a people,” who were grappling with the disorienting knowledge that their leaders–especially Hirohito, who was revered as a god–had led them into disaster.

Harvan did not pose his subjects. Instead, he shot scenes of people trying to recover from the firebombing that destroyed more than half of Tokyo in the last months of the war. Often, it appeared to him that their blank stares showed they still saw in their minds how their city had once looked while they eked out their livings on the ruined streets.

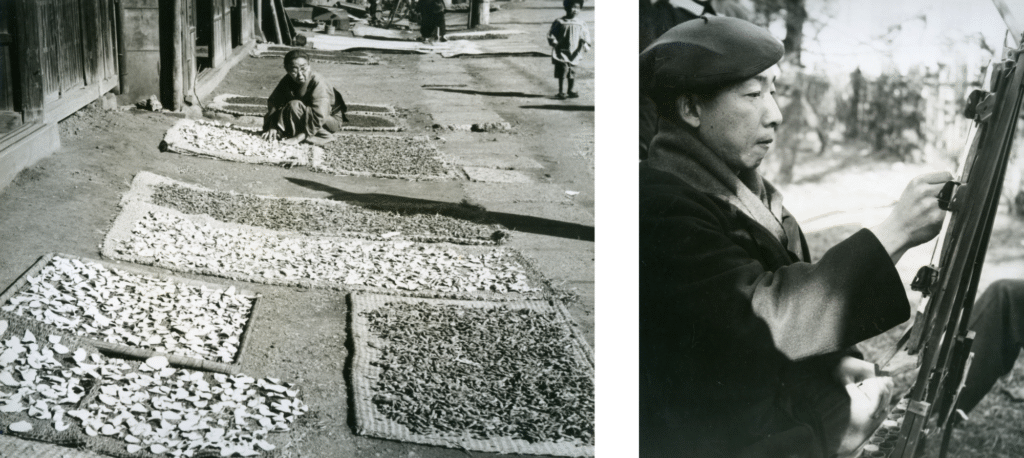

(above, l-r)Dried sweet potatoes were a winter staple food in post-war Japan; Artists earned money by setting up their easels in parks visited by American soldiers, who bought drawings of themselves to send home.

His experiences in Japan shaped his life and philosophy as a photographer for the rest of his life. While shooting the scenes in and around the Lehigh Coal & Navigation’s Panther Valley anthracite mines as a freelancer in the 1950s, he focused on the miners—relatives and neighbors in many cases—as they worked, and as in Japan, he never posed a picture. Again, his goal was to show how his subjects dealt with the challenges of their difficult way of life.

With a family to support, Harvan later worked for twenty-five years in the photography department of Bethlehem Steel, a job that gave him the flexibility to also take thousands of photographs of people and objects. His most famous and enduring works are portraits of the last generation of anthracite miners who worked Number 9 mine until June 1972. Though taken half a world away from Tokyo and more than two decades later, the faces of the Japanese and the Pennsylvanians share one thing—the knowledge that life as they had known it had ended.

George Harvan died in 2002. His bequest of more than fifty years of his printed photographs, transparencies, and negatives are held in the archives of Delaware & Lehigh National Heritage Corridor’s National Canal Museum in Easton.

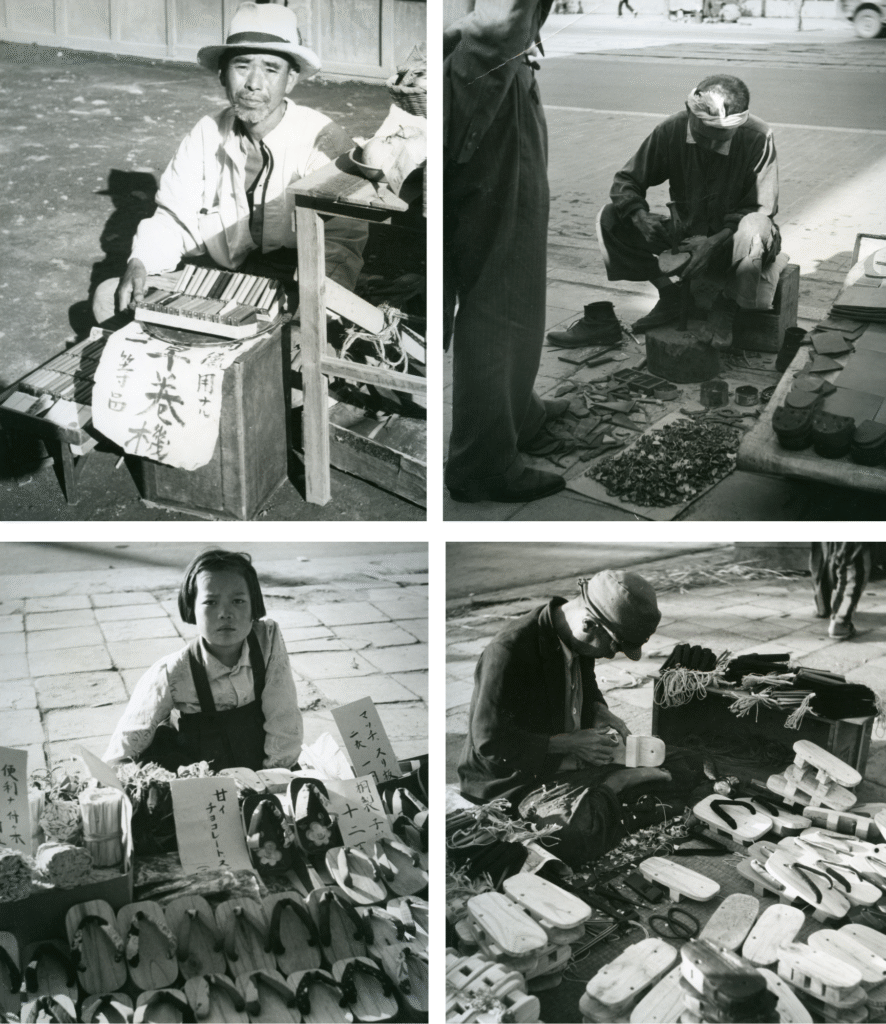

The destruction of the Ginza shopping area of Tokyo in the bombing drove many people selling goods into the streets. Only well-off people had leather shoes, Harvan wrote, so a cobbler who could repair leather shoes could earn good money and might even get some extra help from his customers. Most people wore traditional wooden sandals, like those in some of these photos. The young girl may be selling sandals made by her family; she also appears to be selling bundles of kindling wood for the small stoves residents used for cooking and heat.

Join the Conversation!