The Landscape Suffers and Heals

For years, Lehigh Gap was both an industrial hub and a place of recreation. In the 1800s and early 1900s, Lehigh Gap was a desirable destination for Victorians looking for a respite from the intense summer heat. Newspapers of the 1800s wrote about upcoming travel seasons for city boarders, sometimes even mentioning the number of rooms already booked at Craig’s Hotel, a popular summer resort. Local newspapers highlighted the day trips of their citizens to Lehigh Gap, while salesmen from all over would travel there to sell their wares. Visitors could reach the Gap via the Lehigh Canal, Lehigh & Susquehanna Turnpike, Lehigh Valley Railroad, or the Lehigh & Susquehanna Railroad.

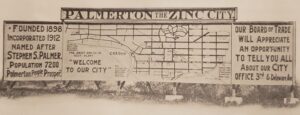

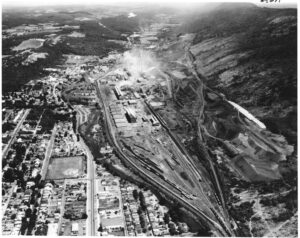

Lehigh Gap became a transportation hub, and with ample access to water, land, and coal, the New Jersey Zinc Company (NJZ) found the site attractive for their zinc smelting plant. The zinc company was originally formed by the merger of The Sussex Zinc and Copper Mining & Manufacturing Company (incorporated in 1848) and The New Jersey Exploring & Mining Company (incorporated in 1849) in Northern New Jersey. Following other small acquisitions and expansions to mines, mills, and plants in Illinois, Wisconsin, and Colorado, the company decided to build a large zinc smelting plant at Lehigh Gap in 1898. Due to the relative isolation of the Gap, the company also built the company town of Palmerton for its workers, named after company president Stephen Squires Palmer.

The company’s first metal plant at Palmerton was modest, designed so the company could experiment with different types of furnaces. Once a suitable type of furnace was chosen, the plant grew rapidly. By the 25th anniversary of the Palmerton plant, it was one of the largest zinc processing plants in the country. Two blast furnaces, built in 1904 and 1906, produced spiegel iron, an alloy of iron and manganese, making more in one day than the company’s furnace in Newark made in a month. Operations at Palmerton expanded into two facilities: the East Plant and the West Plant. In 1923 the company proudly published A Record of Accomplishment, 1848-1923: a Short History of the New Jersey Zinc Company, which provided details on the products they created and their uses. The company’s output was diverse: zinc oxide for pigments and rubber goods, zinc dust for textiles, fireworks, and chemical applications, slab zinc (or spelter) for coating steel, lithopone for white paint, spiegel iron for steelmaking, and sulfuric acid for oil refining and explosives.

This production came at an immense environmental cost. We know today how damaging the effects of this company were to the Lehigh Gap, but back then they either didn’t understand what would happen to the environment or saw it as an unfortunate side effect of progress. Either way, the New Jersey Zinc Company’s steady production of zinc products would forever change the landscape of the area. The furnaces producing spiegel iron released vast amounts of sulfur dioxide into the air. When sulfur dioxide reacts with moisture, it produces sulfuric acid, leading to acid rain and soil contamination. Zinc smelters emitted large quantities of heavy metals. These emissions led to the defoliation of over 3,000 acres of land. Once the vegetation had died, the soil eroded away, creating a ‘moonscape’ remembered by generations. The acid and metals also contaminated the Aquashicola Creek and Lehigh River. With no plants to forage or provide cover, the area lost much of its bird, insect, and mammal populations.

The New Jersey Zinc Company hit its peak between the 1920s and 1950s, but as environmental awareness increased, the company began to decline. Major smelting operations in Palmerton ended in 1980, and in 1983, Palmerton was declared a Superfund Site by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), citing extensive contamination from metals and acid-forming emissions that threatened human and ecological health. To help restore the landscape around Lehigh Gap, both professional and community cleanup strategies were employed. The EPA began by requiring that potentially responsible parties stabilize contaminated soil and revegetate mountain acreage. Grasses tolerant of metal-rich soil were used to anchor the soil and allow other plants the opportunity to recolonize. To prevent additional water contamination, a system was built to divert surface water around a large cinder bank of processed waste created by NJZ. This system also aided in the revegetation of the cinder bank. Other remediation efforts are ongoing. The EPA conducts reviews of site remediation every five years, with the next scheduled for 2027.

The remediation began as a technical challenge but has also become a story of community resilience. In 2002, The Lehigh Gap Nature Center spearheaded restoration initiatives when it began purchasing land around and within the Palmerton Zinc Pile Superfund site. A total of 756 acres were purchased and developed into a wildlife refuge and education center. Local volunteers, schools, and conservation groups partnered with scientists to expand the work started by the EPA, planting native wildflowers, shrubs, and trees as the soil slowly regained its fertility. Trees like the gray birch, sassafras, and aspen established themselves in the restored soil. What was at one time lush forest now thrives as a grassland habitat. Work continues to restore the land, safely and thoughtfully introduce biodiversity, and provide environmental education. A once scarred landscape of bare rock and toxic soil has become a symbol of renewal, demonstrating how damaged ecosystems can recover when science, policy, and community commitment come together.

Resources

Craig’s Hotel. “Advertisement for Craig’s Hotel Summer Rooms.” Allentown Democrat, 3 Sept. 1884, p. 4.

Husic, C.C. “Lehigh Gap: A Story of Degradation and Reclamation.” Cassinia, vol 74-75, 2010-2013, pp 54 – 56.

Husic, D.W., C. Husic, D. Kunkle, and F. Kuserk. 2010. Lehigh Gap Wildlife Refuge Ecological Assessment Part II. Lehigh Gap Nature Center, Slatington, PA.

“Mission and Background: History of LGNC.” Lehigh Gap Nature Center, https://lgnc.org/about-lgnc/about/. Accessed Aug 2025.

New Jersey Zinc Company. A Record of Accomplishment, 1848 – 1923: a Short History of the New Jersey Zinc Company. 1924, New Jersey Zinc Company.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Fifth Five-Year Review Report for Palmerton Zinc Pile Superfund Site, Carbon County, Pennsylvania. EPA Region 3, Sept. 2017, semspub.epa.gov/work/03/2247853.pdf

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Palmerton Zinc Pile Site Profile. EPA, 8 Sept. 1983, https://cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/SiteProfiles/index.cfm?fuseaction=second.Cleanup&id=0300624#bkground

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Palmerton Zinc Pile Superfund Site: Ecological Revitalization of Contaminated Sites Case Study. EPA, Feb. 2011, https://19january2021snapshot.epa.gov/sites/static/files/2018-02/documents/palmertonzinccasestudy-2-2011.pdf

Join the Conversation!