Jose de Navarro and the Atlas Portland Cement Industry

by NCM Historian, Martha Capwell Fox

Last year, we celebrated National Hispanic Heritage Month by introducing Jose de Navarro, who revolutionized the American cement industry by introducing and perfecting the horizontal rotary kiln. That led to the company he founded, Atlas Portland Cement, winning the huge contract for 1.5 million tons of cement needed to build the Gatun Locks on the Panama Canal. Improvements that Navarro and others made to the process made the US into the world’s largest producer of portland cement—most of it made in the Lehigh Valley– in less than 20 years.

Last year, we celebrated National Hispanic Heritage Month by introducing Jose de Navarro, who revolutionized the American cement industry by introducing and perfecting the horizontal rotary kiln. That led to the company he founded, Atlas Portland Cement, winning the huge contract for 1.5 million tons of cement needed to build the Gatun Locks on the Panama Canal. Improvements that Navarro and others made to the process made the US into the world’s largest producer of portland cement—most of it made in the Lehigh Valley– in less than 20 years.

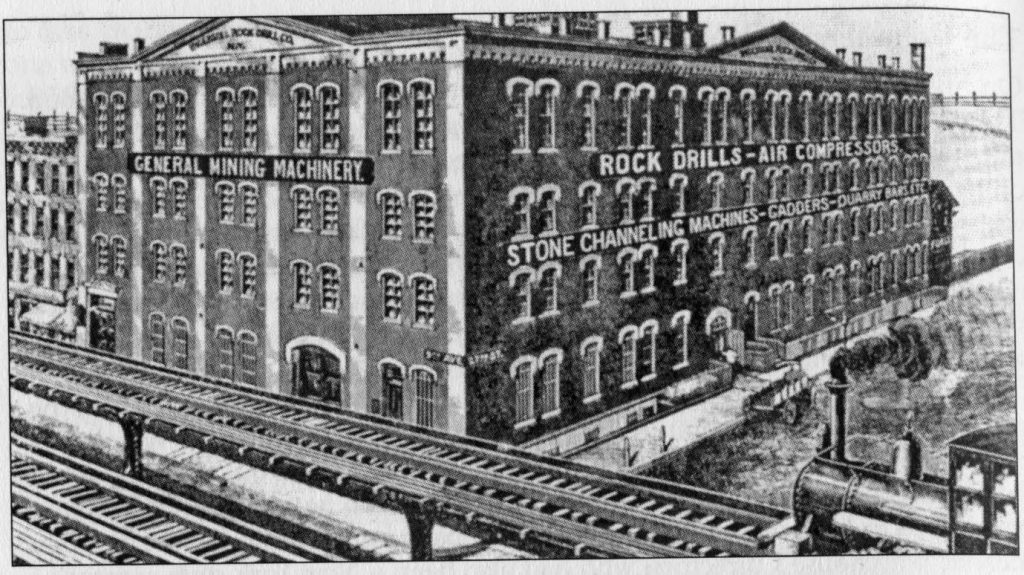

Though Navarro’s pivotal role in cement technology is the most significant part of his 66-year business career, he also founded another company that grew to international status in our area—Ingersoll Rand. Navarro owned a machinery company in New York City under the names of his two “honest, capable foremen,” Henry Sergent and George Collingsworth. In 1871, the firm of Sergent and Collingsworth either built, or repaired (the stories vary) Simon Ingersoll’s first rock drill, and improved on its design with Navarro’s considerable mechanical input.

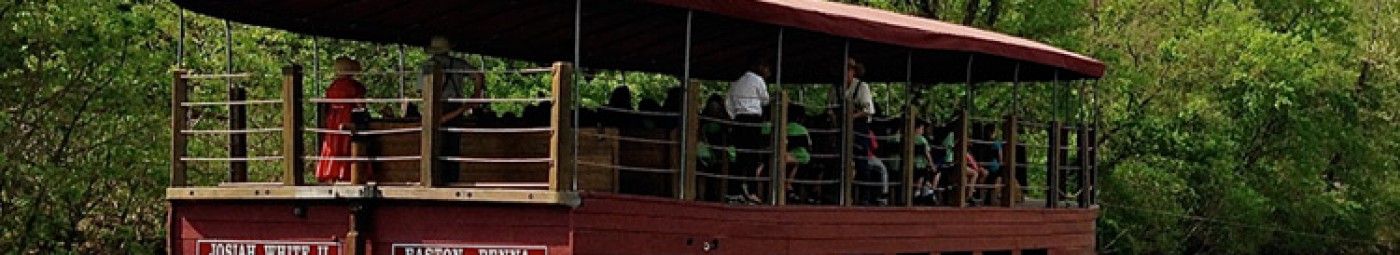

Navarro bought the patent rights to the drill and invested $45,000 in the Ingersoll Rock Drill Company, which Sergent and Collingsworth ran on 9th Avenue in the city while Navarro “kept watching and planning out” the business. The company was very successful; Navarro sold his 90 percent share of it in 1884 for $540,000. The renamed Ingersoll Sergent Drill Company moved to Easton in 1895, constructing a large building that still stands on Lehigh Drive. In 1904, the company merged with the Rand Rock Drill company to become Ingersoll Rand, and relocated to Phillipsburg the following year.

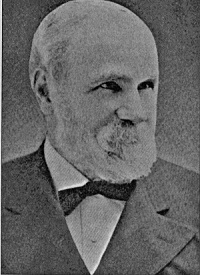

Navarro, born in the Basque region of northwest Spain in 1824, sailed to Cuba alone when he was 15. By age 21, he was a major sugar exporter, but the political instability of the island, a Spanish colony, alarmed him. He moved to New York in 1854 and opened up the US sugar market to Cuban growers who previously had sold their crops only on the island. Then he and his Cuba-based partners went into shipping to other parts of Central and South America, building their own ships which included some of the first American steam-powered iron ocean freighters and carrying US Mail Rio de Janeiro and Buenos Aires.

A man of prodigious energy and resilience, Navarro possessed an astute eye for opportunity, a wily financial mind, and an intellect with a technical bent driven by curiosity. Between the late 1850s and his death in 1909, he amassed a considerable fortune, which he estimated late in his life as being over $3,000,000, while experiencing both monumental achievements (New York’s first successful elevated railway system) and devastating failures (the Central Park Apartments debacle). Navarro was deeply involved in many of the most important technological innovations and corporate enterprises of his day. Though he always behaved as he believed an honorable American businessman should, Navarro never became a citizen, and remained a Spanish subject all his life., and founded the Hispanic Society of America in 1904 with Archer Milton Huntington. Nevertheless, he is little known today—his name does not even appear on the PHMC historical marker near the site of his first cement kiln, but his monuments are every horizontal rotary kiln in use today.

Join the Conversation!