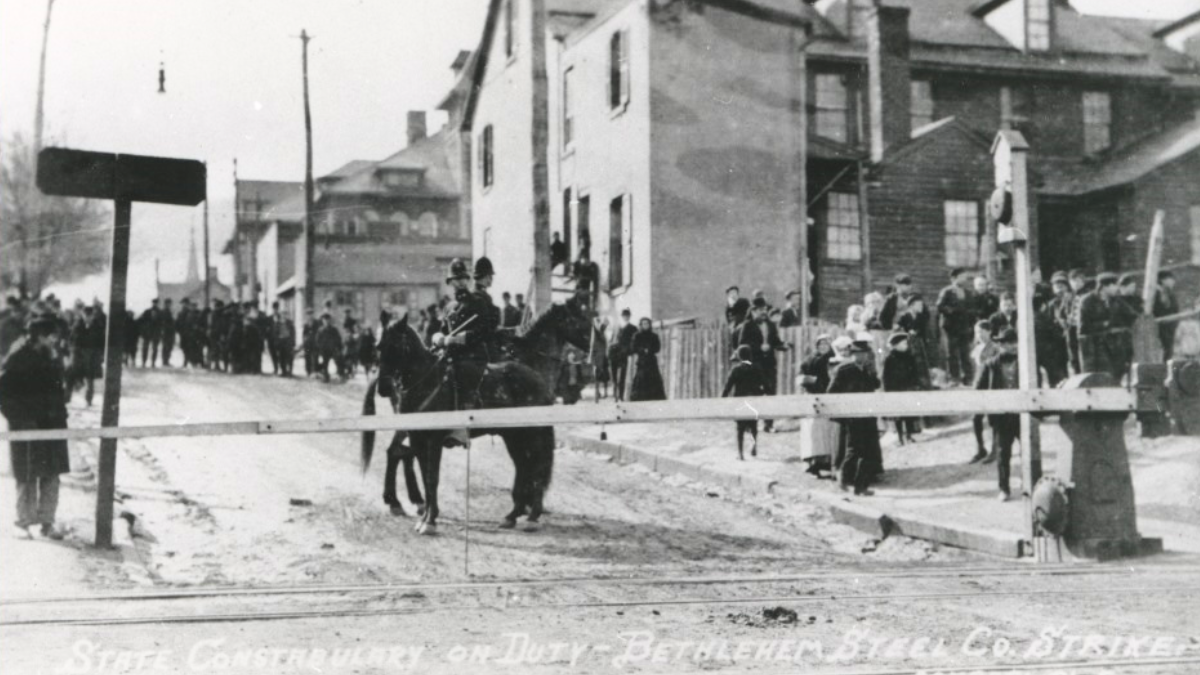

State Police patrolling Bethlehem, 1910.

Bethlehem Steel Strike of 1910

Written by Carter Drake, DLNHC Museum Coordinator

The National Canal Museum hosted a special exhibition from April 4th to December 21st, 2025, titled “To My Much Esteemed Friend”. The exhibition contained a collection of autographed portraits presented to Charles Schwab. Schwab was the executive who formed and ran Bethlehem Steel from 1905 well into the 1920’s. Charles Schwab is usually remembered for his business acumen and turning the Lehigh Valley into one of the nation’s largest steel producing regions. What is often misremembered was Schwab’s difficult relationship with labor. Schwab’s hostility towards organized labor as well as inability to address worker grievances would lead to conflict in South Bethlehem. In 1910, a strike would break out under Schwab’s leadership that eventually led to the creation of the first federal laws regulating the hours of labor.

The strike in February of 1910 had been brewing for years. Conditions at the plant in South Bethlehem were becoming increasingly unpleasant. Setting aside the fact that working at a steel mill was labor intensive, difficult, and dangerous; conditions created by management exacerbated the dissatisfaction felt by the workers at Bethlehem Steel. One of the largest issues for the men working in Bethlehem was insufficient pay. The average hourly rate for company men was around 12½ cents, roughly $4.30 today adjusted for inflation. Not only did the men feel the pay was inadequate, but there were also differing methods of pay at the company that led to competition and confusion. Some men were paid in ‘straight time’, a flat hourly rate. Others received ‘straight piece rates’, a confusing scheme in which workers received a fixed rate per piece completed or tonnage produced. As the Bureau of Labor described it: “Under this system the workman’s compensation is directly in proportion to the amount of work he performs, and he is stimulated to speed up in order to increase his daily or hourly earnings.” The third and arguably most problematic form of compensation was what the company called ‘the time bonus’ system. Workers received an hourly rate, however, each ‘standard piece of work’ had a set time limit. If the worker completed the work within that fixed time limit, they would receive a 20-cent increase to their hourly rate. If completed under the fixed time limit, the worker would receive a 50-cent increase to their hourly rate. This system, in combination with compulsory overtime, frustrated the workers. The speed at which they had to work gradually increased regardless of their individual hourly rate. Adding to the absurdity of the situation, men rarely knew when they would be paid. Pay days were often announced only a day or two beforehand, making financial planning difficult.

The pay was not the only grievance the workers at Bethlehem Steel had with management. Overtime work had been a continual issue for the men in South Bethlehem. The company essentially required certain employees to report to work on Sundays. Work on Sunday was nominally ‘optional’, though workers who refused the request on Saturday would sometimes find themselves out of work on Monday. What frustrated the laborers further was the fact that they received no additional compensation for overtime, only their regular rate. By 1910 over a quarter of the staff were working 7 days a week. Even if one did not work on a Sunday, the weekly hours were unforgiving. Workers in the machine shop worked an average of 57 hours a week; blast furnace and boiler workers worked a grueling 84 hours a week. With such demanding hours, it is understandable that workers would hope to avoid being required to labor an additional day of the week without appropriate compensation.

It is hard to tell when or for how long the workers at the South Bethlehem considered taking action. The Bureau of Labor indicated in its report on the strike that due to the lack of organized labor in Bethlehem, it was impossible to “determine just to what extent there was opposition to overtime and extra Sunday work, nor for how long a period, whatever opposition there might be, had been developing.” What is clear is that in January of 1910, these grievances were significant enough for the workers to act out.

On the 30th of January a workman named Henry Schew decided not to come into work on Saturday. Schew hoped that by not working on Saturday, he would not be asked to work on Sunday. Upon his return to South Bethlehem on Monday, word got out as to why he did not show up over the weekend. Once his foreman discovered the truth, he was fired on the spot. Dissatisfied with the way their fellow machinist was treated, the workers at shop No. 4 decided to put together a committee to advocate for Schew and address their shared grievances. On February 4th, three men approached the foreman and shop superintendent to request the rehiring of their fellow machinist, an end to Sunday work, and a reduction of overtime in the machine shops. The three men were fired shortly thereafter. The firing of the men advocating for Henry Schew would lead to the protest of the machinists in shop No. 4. The protesters attempted to rally the other shops to their cause, getting shop No. 3 and No. 6 to join them. The men were ejected from the premises by company policemen before they could gather more machinists. The strikers formed a crowd in a vacant lot adjacent to the plant. As mentioned earlier, the vast majority of workers at Bethlehem Steel were not members of a trade union and had very little experience organizing. For the time being, their protests addressed the problems company machinists were facing, not the average worker. It was not until unaffiliated trade unionists in Bethlehem invited members of the Federation of Labor to assist in organizing Bethlehem Steel strikers that the scope of the strike would change. Basing themselves in South Bethlehem’s town hall, the strikers began to formulate a list of demands that would incorporate the needs of other positions at Bethlehem Steel. What started as a protest concerning the practices in the machine shops would evolve into a company-wide strike for better working conditions.

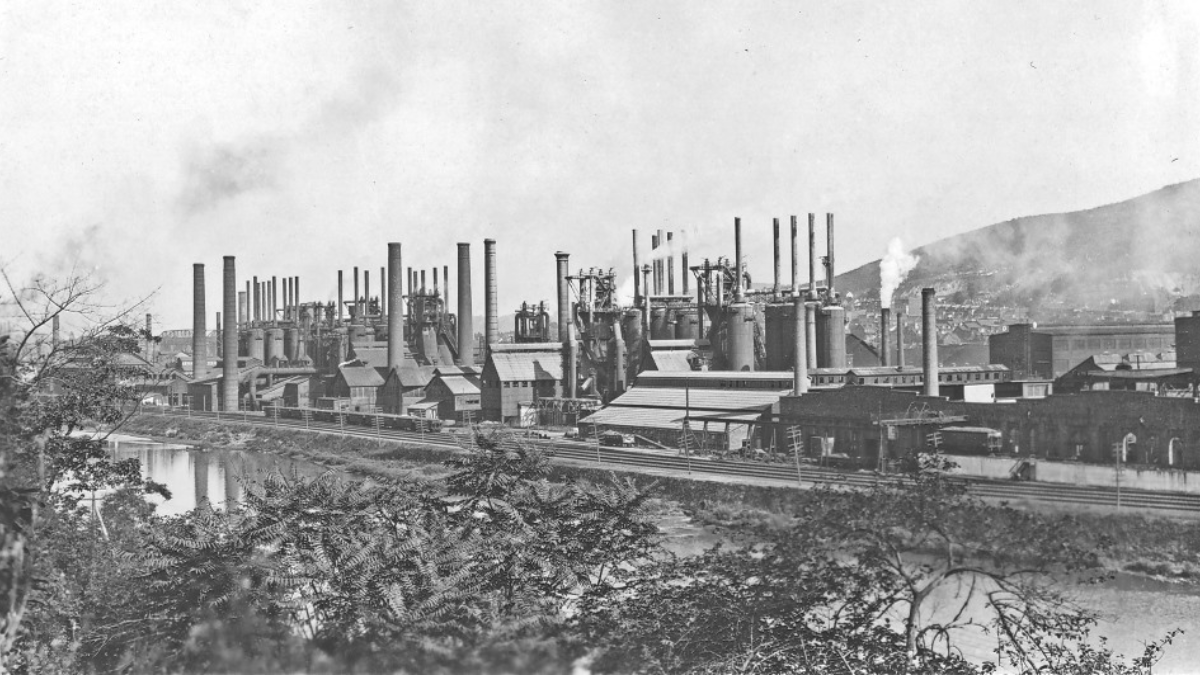

Bethlehem Steel from Nisky Hill, 1910

Even though the strike technically began on the 4th of February, the strikers had yet to put on a demonstration. Occupied with their own committees and internal discussions on what to demand from the company, little transpired until February 24th, when the strikers organized a parade. The parade itself was a peaceful event. Not a single arrest was made, and the only incident of violence was when strikers pulled a worker from a tram to destroy his lunch pail. Much to the chagrin of Bethlehem Steel management, the local authorities were not threatened by the parade and felt that they had provided an adequate level of security. Management felt threatened. After a brick crashed through the window of the plant’s superintendent, they felt the need to appeal to the state police. On the morning of February 26th, 24 state police officers arrived from Philadelphia.

The state police managed to alienate nearly every party in Bethlehem apart from the company. They also behaved poorly. Random beatings were commonplace, and arrests were arbitrary; they policed through violence. Local authorities complained of the overbearing presence of state police and their penchant for using force. The Bureau of Labor’s report on the strike noted the police’s role in the violence, blaming them for escalating tensions in South Bethlehem. In that same report, the former and then acting police chiefs of South Bethlehem made statements blaming the state troopers for harassing the citizens of South Bethlehem and making things generally worse. They described instances of troopers attacking the citizens of Bethlehem unprovoked, making arrests without cause, ignoring the local authorities, and taking ‘prisoners’ to the Bethlehem Steel plant as opposed to the local jail. There was even an incident in which a state policeman fired his weapon into a crowded bar, killing one person and injuring another. That same document contained the Pennsylvania state police report of the strike from their perspective. Unsurprisingly, the state police were convinced that all accusations of wrongdoing were exaggerated, and that they honorably dispensed justice.

When the State police were called into Bethlehem, the company shut the plant down until the 28th. Expecting a quick end to the strike, the company was alarmed to find that nearly 2,200 employees refused to return to work. A few days later, on March 5th , the strikers published a letter to the company in the Bethlehem Times listing their demands. The strikers requested a raise in wages, time and a half for overtime, work on Sundays, and paid holidays, just cause for firings, minimum wages for apprentices, and a standard 10-hour workday. The next day, the company’s reply would be published. In the open letter to the strikers, Charles Schwab refused to negotiate with the striking workers, arguing that he can only negotiate with workers employed by the company, and by virtue of striking, they were no longer employees of the Bethlehem Steel Company.

As the strike continued through March, management caved and began to meet with the strikers. A committee of workers was formed to negotiate a new contract with the company. The committee was not formally recognized by Bethlehem Steel as an official body representing the workers. Schwab himself was present at the meetings, though his presence did not alter the stalemate. The company was now only willing to make concessions that were no longer acceptable to the strikers. Management was only willing to compromise on the demands made by the machine shops back in the first weeks of February. With the strike no longer confined to the machinists in the shops, the terms offered by management were not enough to placate the strike committee.

As negotiations continued to flounder, both sides were becoming increasingly desperate for a conclusion to the strike. In mid-March, strikers had been going without financial support for weeks. The men were struggling to feed themselves let alone organize against one of the nation’s largest steel producers. Meanwhile, Bethlehem Steel was losing out on potentially lucrative contracts with the Federal Government as its workforce sat idle. Controversy grew around the company, especially after the murder of Joseph Szambo by state troopers on the 26th of February. By April the strike and shooting in Bethlehem had become national news, and the company was facing growing scrutiny. Labor organizers and Congressmen pointed out that a company that had received tens of millions in defense contracts, with such glaring labor problems, would not only lead to scandal but also posed a threat to the nation’s ability to defend itself.

Framing the strike as an issue of national security was an effective way for labor organizers to get Congressional attention. In the closing days of March, organizers from the American Federation of Labor met with Congressman A. Mitchell Palmer, requesting that the Bureau of Labor investigate conditions at the plant. By this time, several members of Congress advocated legislation that forced government contractors to adhere to an 8-hour workday. Palmer was one of them, and he agreed to start a federal investigation into the conditions at Bethlehem Steel. While the Bureau’s probe was a step in the right direction, the strikers were feeling Schwab’s pressure. On the 30th of March, he threatened the government of Bethlehem to stop allowing the strikers to headquarter in the town hall or he would shutter the entire plant. His threats worked, and strikers complained of being shut out of every public building in the town. By April, four months of striking was taking its toll, and the men were running low on funds and food. As things grew increasingly desperate for the strikers, they appealed to higher powers for help.

Realizing that the Bureau of Labor’s report was still some time away, and not guaranteed to produce results, leaders of the strike appealed to the Oval Office. President William Taft was not as receptive as they had hoped. The president wished to await the report from the Bureau of Labor before making any official decision. Unfortunately for the striking steelworkers, the report would not be released until the 4th of May. The report on Bethlehem Steel confirmed the striker’s grievances; it was found that over half of the workforce at Bethlehem was working 12-hour shifts. The report was widely circulated, and the conditions described caused outrage in both the public and Washington. Disappointingly for the men on strike, nothing was done to immediately address their concerns, and the increasingly hungry and desperate workers were forced to return to work. On May 18th, 1910, the leaders of the strike voted to return to Bethlehem Steel.

Although the strike was technically unsuccessful, the labor report that came out of Bethlehem sent shockwaves through the steel industry. Newspapers nationwide bashed Bethlehem Steel’s treatment of its workers and called for reform. Legislators on both local and federal levels moved to pass bills concerning labor hours for government contractors. Investigations into the steel and iron industry nationwide began shortly after the report’s publication. Nearly a year later, in 1911, a Pennsylvania State Representative from Lackawanna County introduced the state’s first law regulating the hours of “mechanics, working-men, and laborers”. Though that bill was not passed, some success was seen at a federal level. HR 9061 was signed into law in June of 1912 by President Howard Taft. The bill was the first federal law regulating the working hours of an industry in American history. With its passing, if a company were to sign a contract with the federal government, they were required to have their employees work 8-hour days.

The 1910 Strike at Bethlehem Steel objectively failed. The men who had left the machine shops in protests of the conditions faced there would end up returning to them with little to show for it. While the strike may have failed, its lasting impact on labor should not be ignored. Their struggle inadvertently led to a wave of federal probes into the workplaces of government contractors. It resulted in some of the first legislation designed to protect laborers through the regulation of working hours. The government’s report on the Bethlehem Steel strike would be referenced by future legislators when proposing laws that regulated the workplace for years after the strike. Equally as important, the strike, and its coverage in the press, led to a broader discussion taking place in American society that addressed the relationship between work and personal time. Without the efforts made by the strikers in 1910, the steel industry in the United States may have continued to operate with little to no oversight well into the 20th century.

Sources

Ennis, Ron W. “Bethlehem Steelworkers, the Press, and the Struggle for the Eight-Hour Day.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, December 7, 2022. https://journals.psu.edu/phj/article/view/63296.

U.S. Congress. Senate. Committee on Education and Labor. Eight-Hour Law: Hearings before the Committee on Education and Labor, United States Senate, Sixty-Second Congress, on H.R. 9061, A Bill Limiting the Hours of Daily Service of Laborers and Mechanics Employed upon Work Done for the United States, for any Territory, or for the District of Columbia, and for Other Purposes. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1912. HathiTrust Digital Library.

U.S. Congress, Senate. Committee on Education and Labor. Report on the Strike at Bethlehem Steel Works, South Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Prepared under the direction of Chas. P. Neill. Commissioner of Labor. Washington, DC, Government Printing Office, 1910. Lehigh University Library Digital Collections.

Related Articles

The Beginning of Bethlehem Steel

Springtime, Wartime: Bethlehem Steel, 1942

Death of a Giant: 25th Anniversary Commemoration of the “Last Cast” at Bethlehem Steel

Join the Conversation!